HRV Anatomy and Physiology (1 Hour)

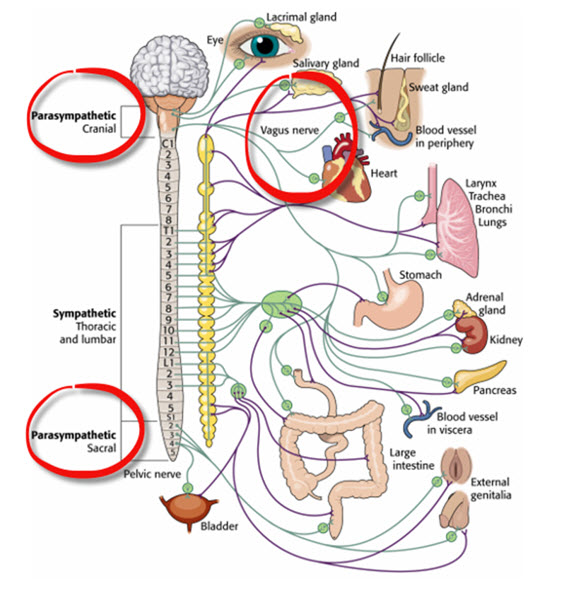

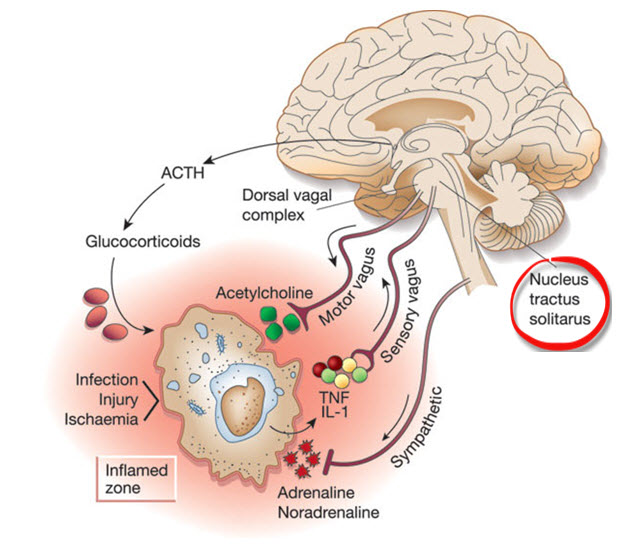

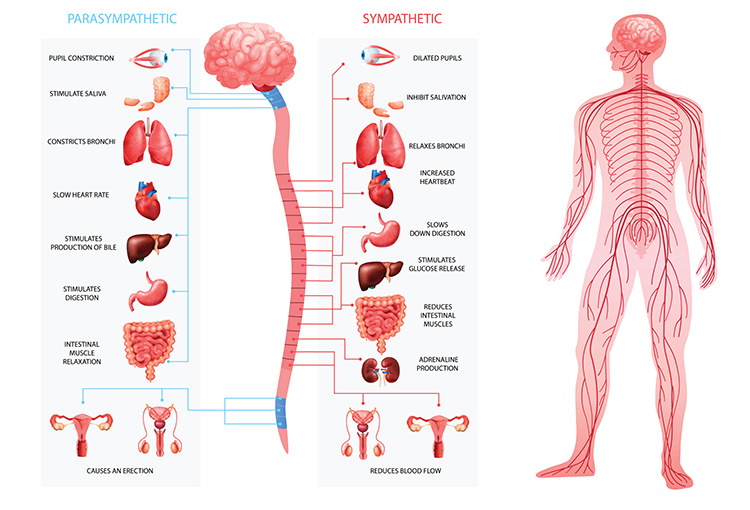

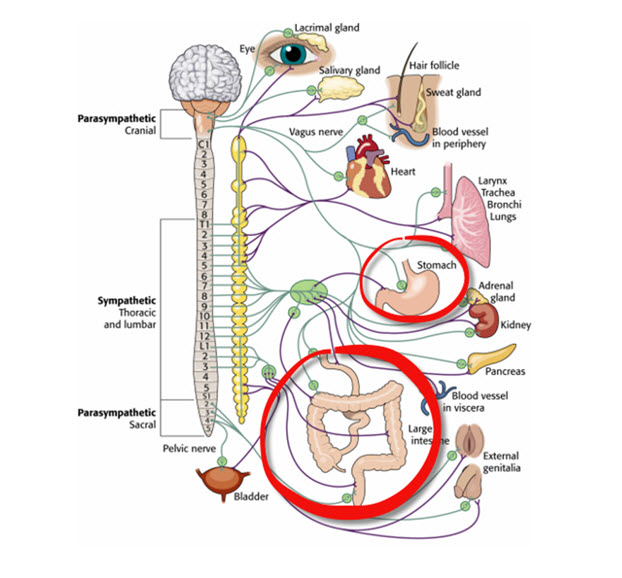

Biofeedback interventions like heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB) target the cardiovascular system to treat disorders as diverse as anxiety, depression, essential hypertension, migraine, post-traumatic stress disorder, Raynaud's disorder, and stress. Biofeedback monitors blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), heart rate variability (HRV), pulse wave velocity, temperature, and blood volume pulse modalities. There has been a paradigm shift in treating disorders like depression and heart failure. Clinicians increasingly teach clients to enhance HRV through exercises that strengthen parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) tone. PNS activity is also called vagal tone because the vagus is the primary component of this autonomic branch (Breit et al., 2018).

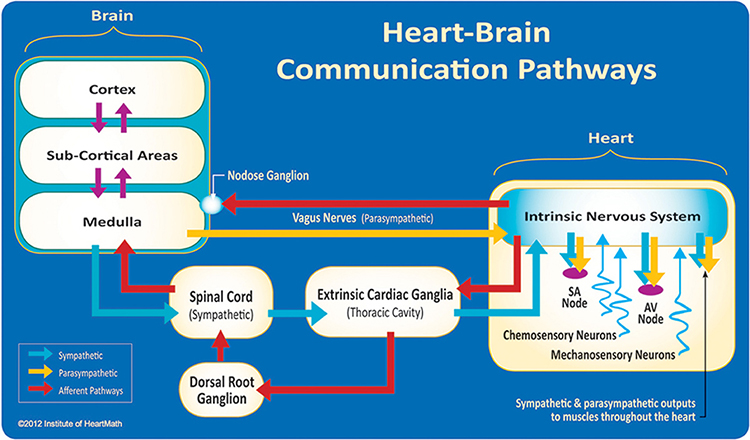

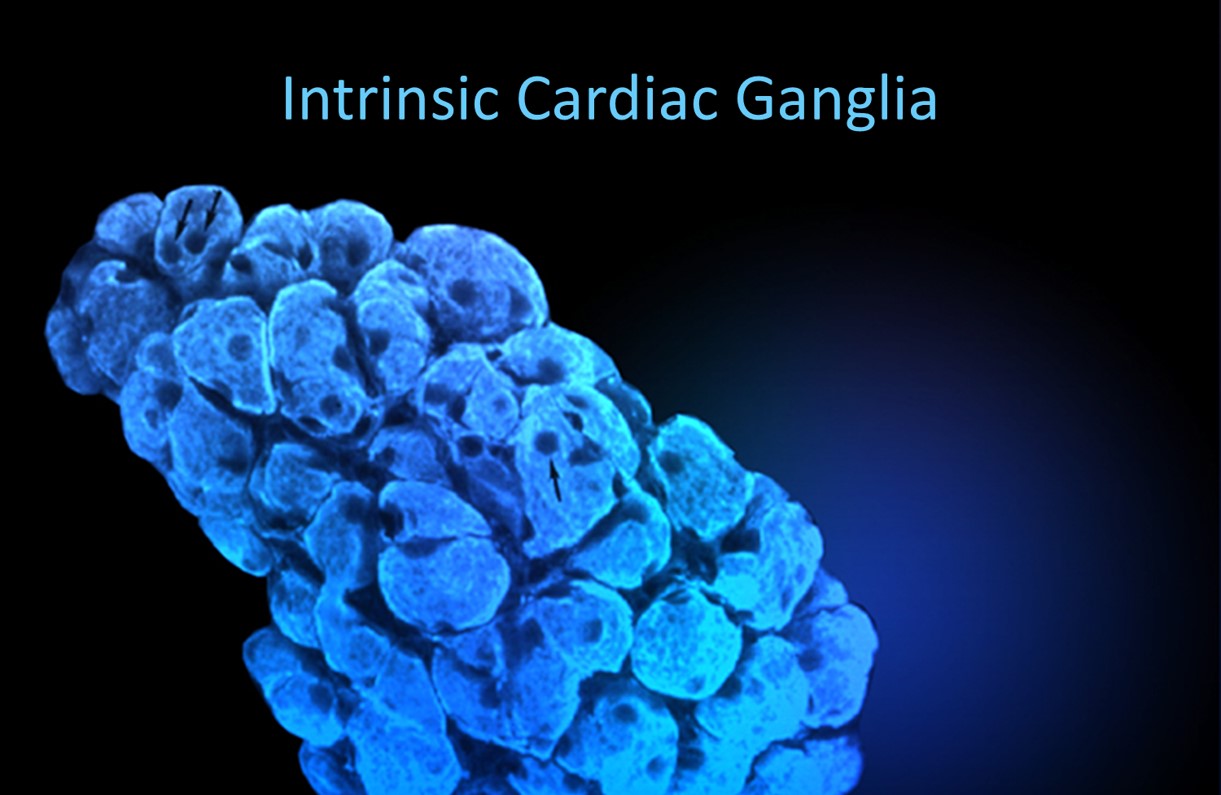

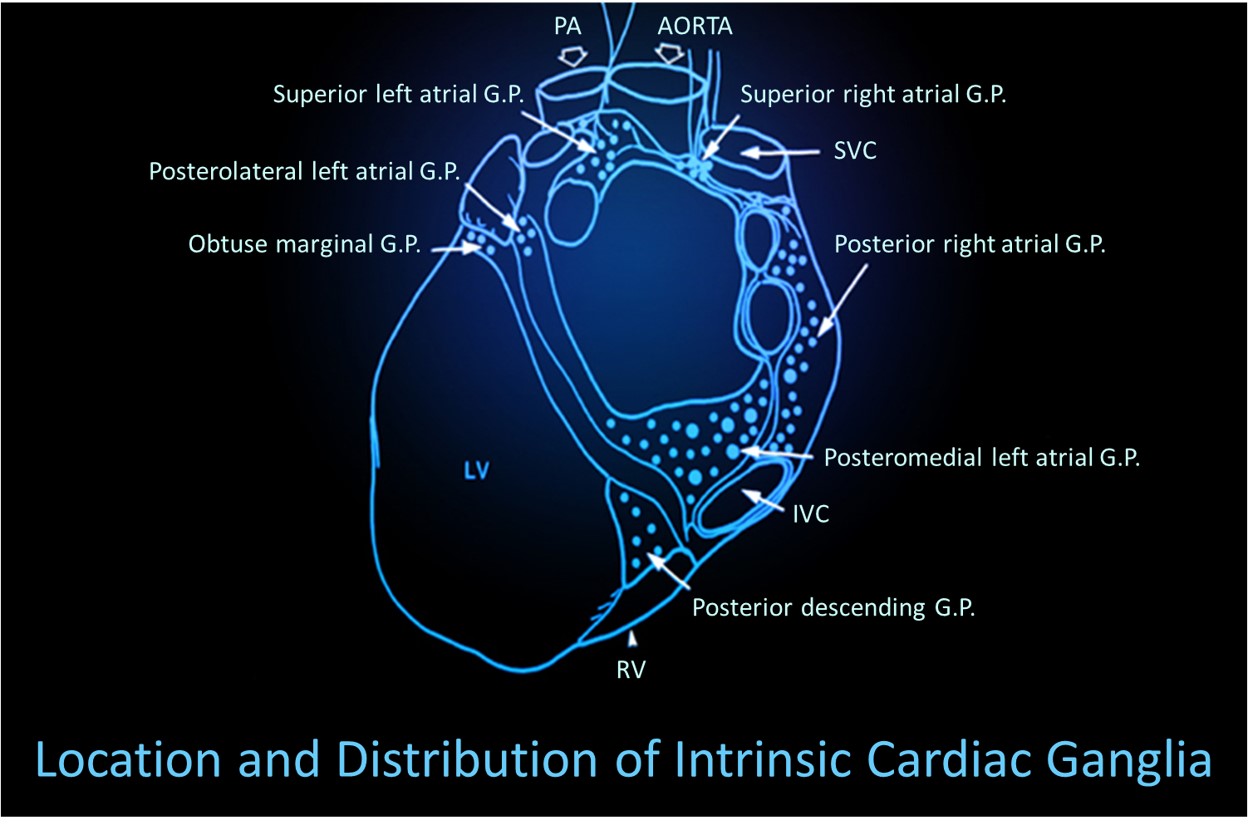

The brain receives more afferent projections from the heart than any other organ. Emerging evidence suggests that the heart's intrinsic nervous system has extensive bidirectional connections with the brain (MacKinnon et al., 2013; Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).

Researchers increasingly recognize the importance of HRV as an index of vulnerability to stressors and disease.

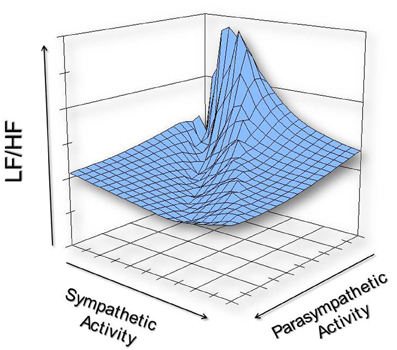

The PNS and baroreceptor system produce brief (≤ 5 minutes) resting HRV without a sympathetic contribution.

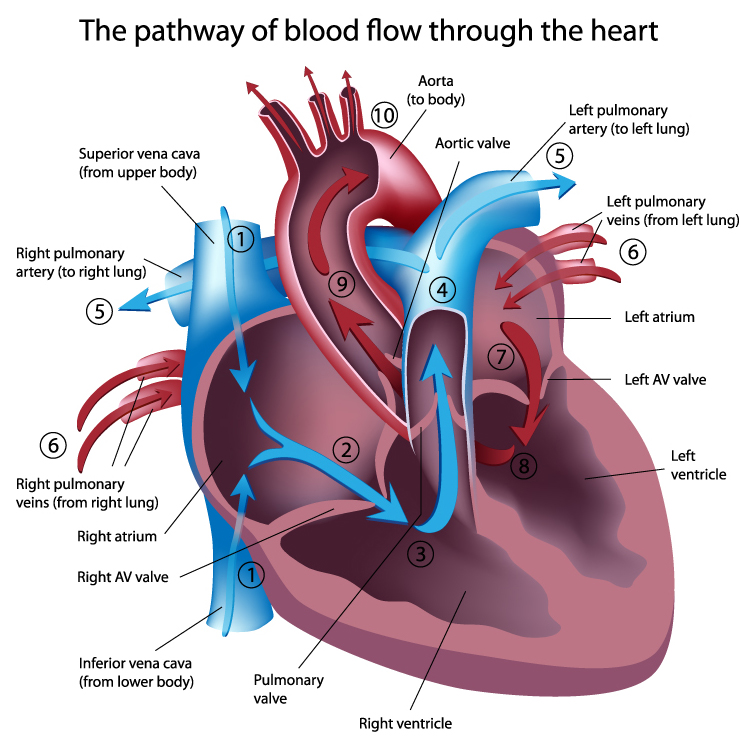

Patients can learn to increase the healthy variability of their hearts to treat disorders like anxiety, asthma, depression, hypertension, and irritable bowel syndrome. HRV biofeedback training can help patients restore a healthy dynamic balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.Temperature is one of the most widely trained modalities. Our understanding of the mechanisms underlying hand-warming and hand-cooling, while still incomplete, has radically changed due to landmark studies by researchers like Robert Freedman. These findings underscore the complexity of the cardiovascular system. The graphic below depicts blood flow within the heart. Graphic © Sebastian Kaulitzki/Shutterstock.com.

Two patterns, coupling and fractionation, describe changes observed when monitoring subjects. In response coupling, responses change together (HR up, BP up). In response fractionation, responses change independently (HR down, BP up).

Coupling and fractionation reflect the multiple, independent processes that jointly produce these physiological measures. Healthy systems operate nonlinearly (unpredictably) to adapt to rapidly changing demands. Whether responses couple or fractionate during a specific observation period depends on the complicated interplay of subject, task, and environmental variables.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Cardiovascular Anatomy Overview © BioSource Software LLC.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses HRV Anatomy and Physiology (1 hour) and covers Cardiac Anatomy and Physiology, Respiratory Anatomy and Physiology, and Autonomic Nervous System Anatomy and Physiology.

A. CARDIAC ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

This section covers Arteries, Three Measures of Peripheral Blood Flow, Veins, Capillaries, Arteriovenous Anastomoses (AVAs), Blood Pressure, the Heart, and Heart Rate Variability.

Arteries

Arteries carry blood away from the heart.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Arteries © BioSource Software LLC.

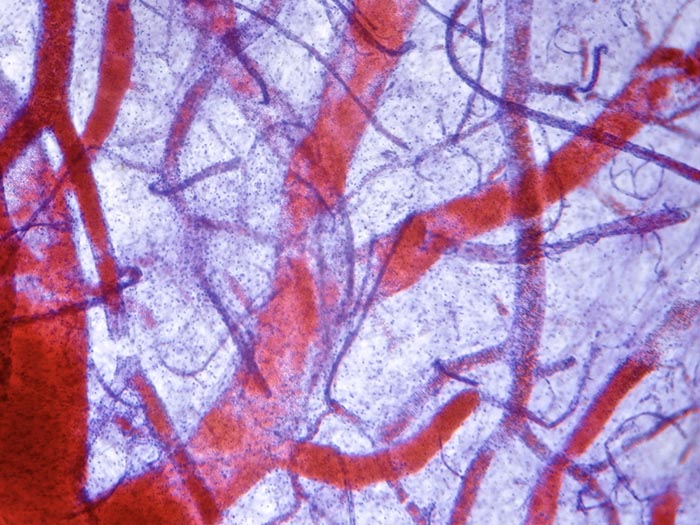

Arteries appear red in the photomicrograph © Anna Jurkovska/Shutterstock.com.

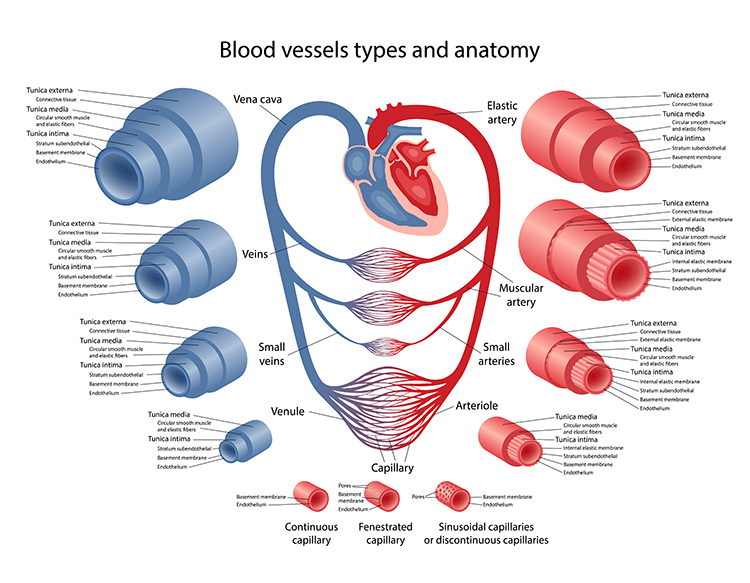

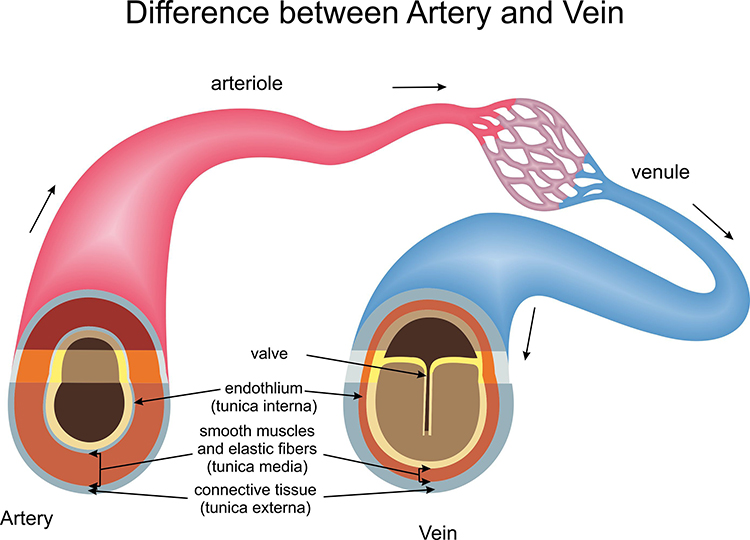

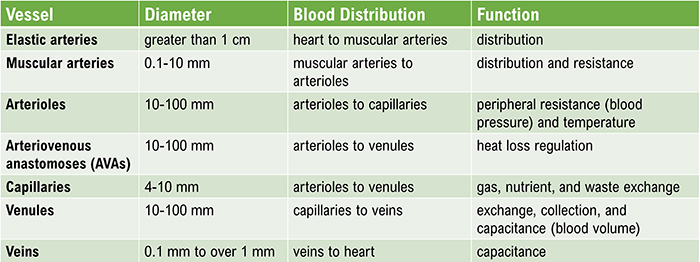

Check out the Khan Academy YouTube video Arteries vs. Veins - What's the Difference? Arteries are divided into elastic, muscular, small arteries, and arterioles. Graphic © Olga Bolbot/ Shutterstock.com.

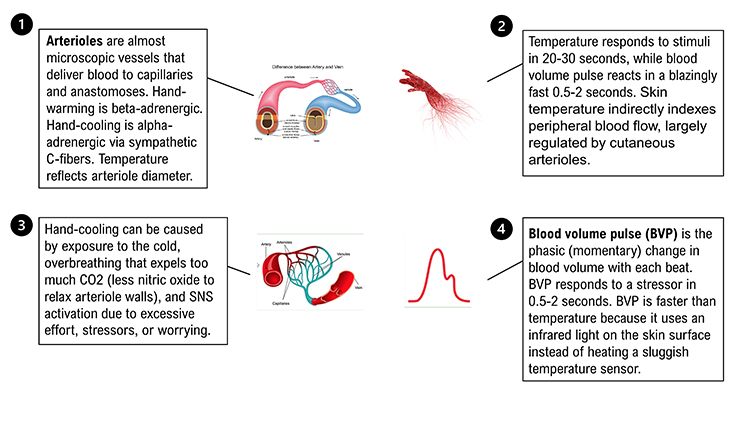

Elastic arteries are large arteries like the aorta (shown below) that distribute blood from the heart to muscular arteries. Medium-sized muscular arteries (like the brachial artery) circulate blood throughout the body. Arterioles are almost microscopic (8-50 microns in diameter) that deliver blood to capillaries and anastomoses. Graphic © McGraw-Hill.

Arterioles are responsible for roughly 50% of peripheral resistance through their narrow diameter, contractility, and massive surface area. The video below shows red blood cells traveling through a pulsating arteriole.

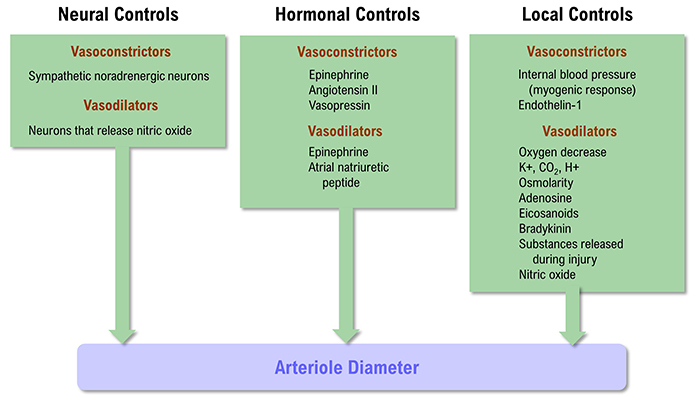

The control of arteriole diameter, which is crucial for regulating BP and hand temperature, is highly complex. Neural, hormonal, and local controls cooperate to regulate blood flow through arterioles. These control mechanisms play varying roles across our body's organs.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Factors That Control Arteriole Diameter © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic below was adapted from Widmaier et al. (2019).

All arteries have three layers or tunics surrounding a hollow lumen or center. The tunica interna (innermost layer) responds to epinephrine (E) and norepinephrine (NE) with vasodilation (increase in lumen diameter and blood flow) in digits like the fingers.

The tunica media (middle layer) is composed of smooth muscle and elastic fibers controlled by sympathetic constrictor fibers (C-fibers). This is a site of neurally-controlled vasoconstriction (decrease in lumen diameter and blood flow) in the digits.

Finally, the tunica externa or external layer comprises a connective tissue sheath.

Separate mechanisms produce hand-warming and hand-cooling. Hand-warming involves releasing a beta-adrenergic hormone and nitric oxide at the tunica interna. Hand-cooling is mediated by vasoconstrictor hormones and the firing of sympathetic C-fibers at the tunica media.

Three Measures of Peripheral Blood Flow

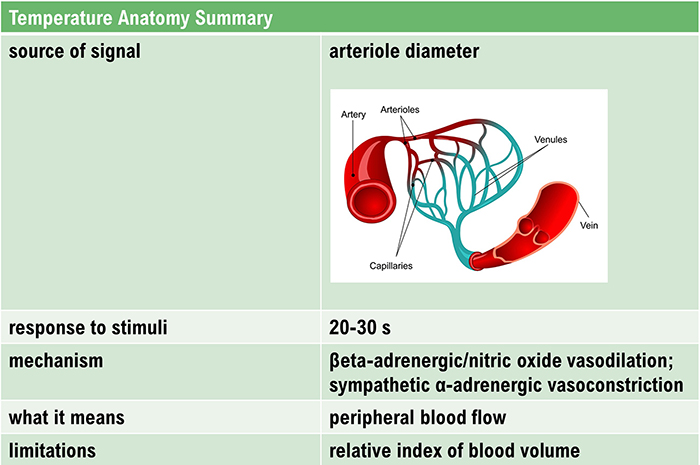

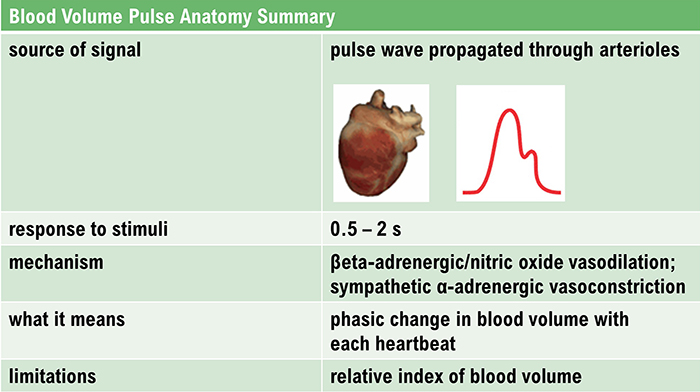

Temperature, blood volume pulse, and pulse wave velocity depend on blood movement through arteries. Temperature and blood volume pulse provide relative measures of peripheral blood flow.

Temperature responds to stimuli in 20-30 seconds, while blood volume pulse reacts in a blazingly fast 0.5-2 seconds.

Temperature

Skin temperature indirectly indexes peripheral blood flow, primarily regulated by cutaneous arterioles (Peek, 2016).Listen to a mini-lecture on Hand Temperature © BioSource Software LLC.

Graphic © Chawalit Banpot/Shutterstock.com.

Temperature is a gradual tonic index of blood flow. Following a stressor, it may take temperature 20-30 seconds to fall since arterioles must constrict, tissue perfusion with blood must drop, and a sensor called a thermistor must register this change.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Hand-Cooling © BioSource Software LLC.

"Temperature is the modality most vulnerable to effort" (Khazan, 2019, p. 90). Since blood volume pulse and temperature monitor the same underlying physiology, "trying" can produce large-scale disruptions in this modality as well.

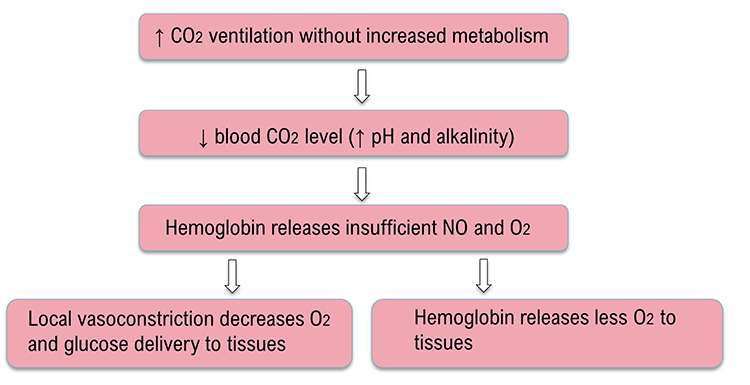

Exposure to cold temperatures, overbreathing, trying too hard, stressors, and worrying can trigger hand-cooling. CO2 loss reduces nitric oxide release, which is needed to relax arteriole walls.

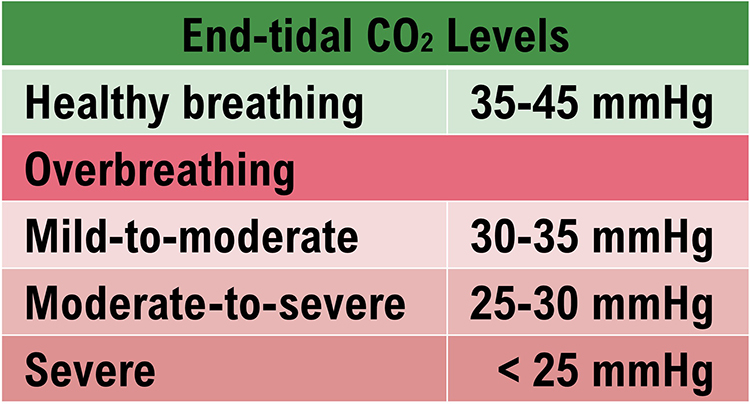

Caption: Overbreathing graphic adapted from Inna Khazan.

Blood Volume Pulse

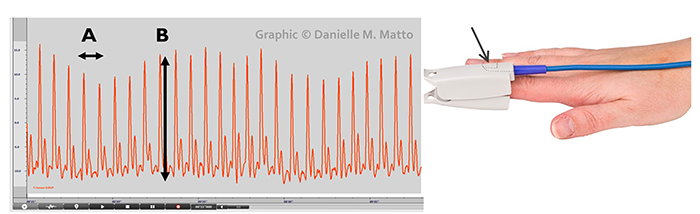

Blood volume pulse (BVP) is the phasic (momentary) change in blood volume with each heartbeat. It is the vertical distance between the maximum value (peak) and the minimum value (trough) of a pulse wave and is measured by the photoplethysmograph (PPG).Listen to a mini-lecture on Blood Volume Pulse © BioSource Software LLC.

BVP responds to a stressor in 0.5-2 seconds. BVP is faster than temperature because it shines an infrared light on the skin surface instead of using a sluggish temperature sensor.

The large-scale BVP changes in hands that are not cold can help clients when hand-warming stalls since BVP provides higher-resolution feedback.

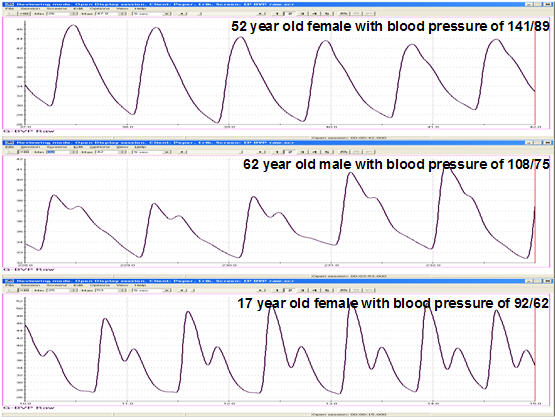

The shape of the BVP waveform can indicate loss of arterial elasticity, and decreased pulse transit time is associated with aging, arteriosclerosis, and hypertension (Izzo & Shykoff, 2001). Peper, Harvey, Lin, Tylova, and Moss (2007) compared BVP waveforms and BP values for two parents and their teenage daughter in the recordings below.

Caption: Comparison of finger BVP recording of parents (62-year-old father and 52- year-old mother) and child (17-year-old daughter). The mother has borderline hypertension. The absence of the dicrotic notch in the borderline-hypertensive (top) tracing suggests a stiffening of the arteries indicating increased BP.

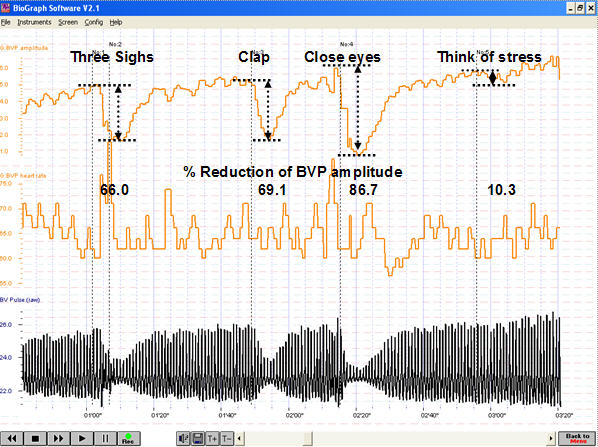

BVP amplitude can provide valuable information about a client's cognitive and emotional responses, as shown in the recording below from Peper, Harvey, Lin, Tylova, and Moss (2007).

Caption: This figure shows psychophysiological responses during a standardized stress protocol. The participant’s responsiveness to internal and external physical and emotional stressors is vividly depicted in the variations of BVP amplitude. The pattern portrays decreases in amplitude in BVP signal in response to prompts such as sighs and claps that triggered SNS activation. In this participant, eye closure during the protocol evoked an unanticipated and large decrease in the BVP amplitude compared to any of the physical or imagined stress conditions. This unanticipated decrease in BVP may be interpreted as a kind of anticipatory anxiety.

Below is a blood volume pulse (BVP) display. Note the small dicrotic notch following the peak of each waveform. The reduction or disappearance of a dicrotic notch may indicate the loss of arterial flexibility seen in arteriosclerosis.

When a client is successful in hand-warming, temperature has two advantages over BVP: it is measured in absolute units and changes more gradually. Blood volume pulse and temperature display © BioSource Software LLC.

Pulse Wave Velocity

Ejection of blood from the left ventricle during systole produces a pulse wave. Pulse wave velocity (PWV) is the rate of pulse wave movement through the arteries. Practitioners measure PWV by placing pressure transducers (motion sensors) at two points along the arterial system (like the brachial and radial arteries of the same arm). The interval required for the pulse wave to move between these points is called transit time (TT). Pulse wave velocity is used as an indirect measure of BP change. During stress tests, researchers have reported correlations with average and systolic (but not diastolic) BP changes.Veins

Veins are blood vessels that route blood from tissues back to the heart. Veins contain the same three layers found in arteries.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Veins © BioSource Software LLC.

These layers are thinner in veins due to lower pressure. The graphic below compares arterial (top) and venous (bottom) structures. Graphic © NelaR/ Shutterstock.com.

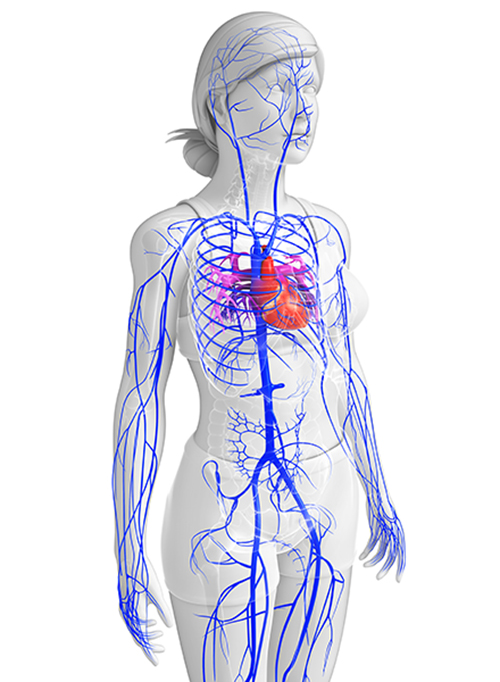

Smooth muscle allows venules to adjust diameter actively. The venous system is shown below in blue. Graphic © S K Chavan/ Shutterstock.com.

A venule is a small vein (less than 2 millimeters in diameter) that collects blood from capillaries and delivers it to a vein. The low return pressure in these vessels requires valves that prevent backward blood flow. Venules play an essential role in controlling return blood flow to the heart due to narrow diameter, contractility, and extensive surface area. Graphic © McGraw-Hill.

Capillaries

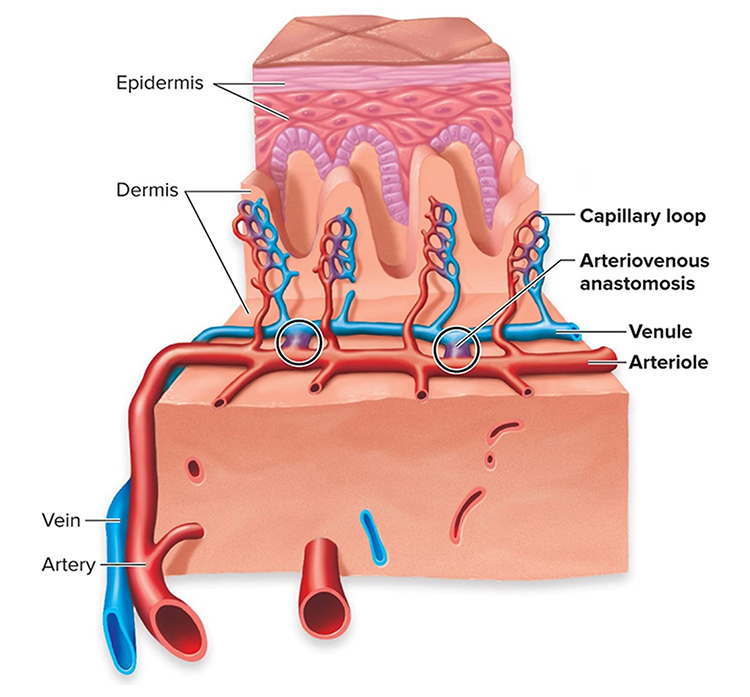

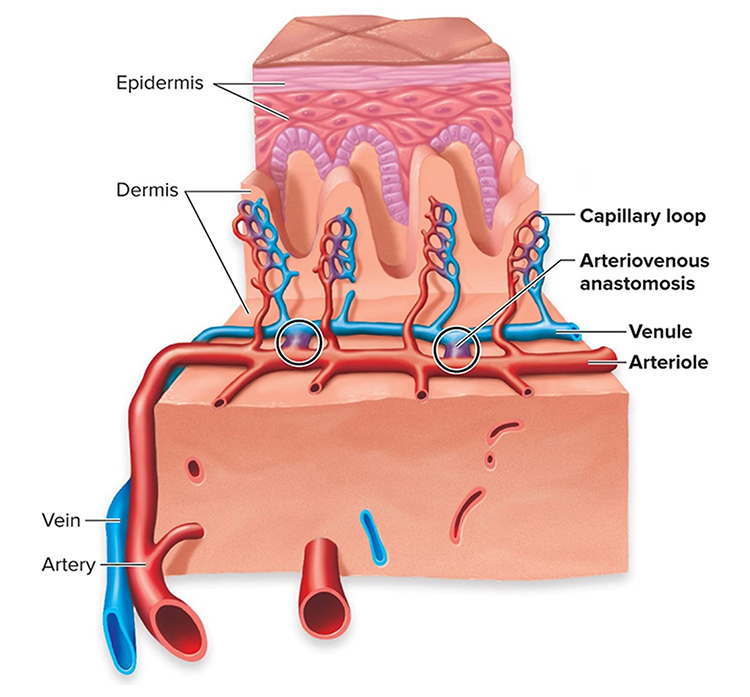

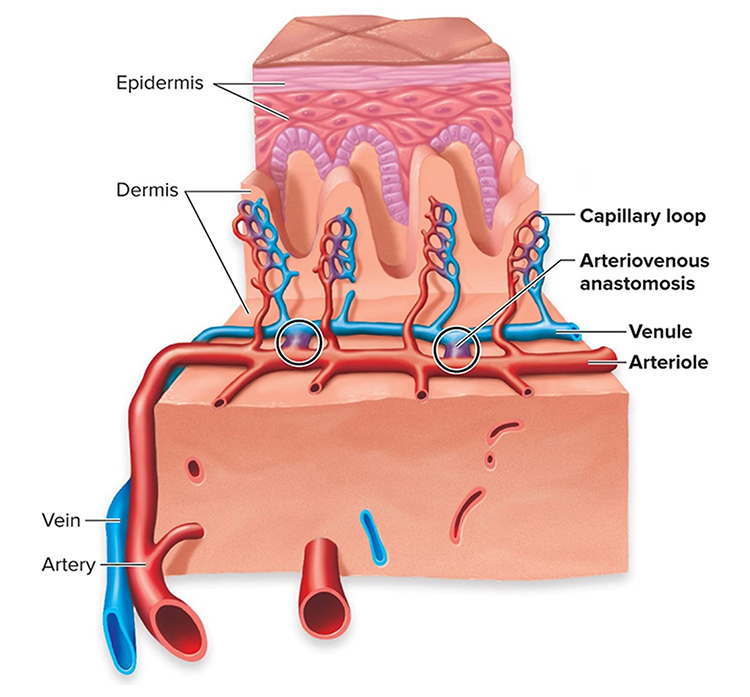

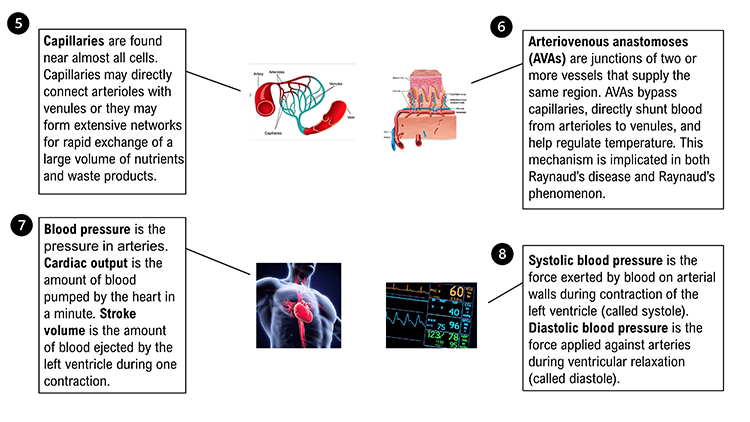

Capillaries may directly connect arterioles with venules or form extensive networks to rapidly exchange a large volume of substances (nutrients and waste products).

Listen to a mini-lecture on Capillaries © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © McGraw-Hill.

A capillary generally consists of a single layer of endothelium and basement membrane. Change in capillary diameter is passive due to the absence of a smooth muscle layer. True capillaries extend from arterioles or metarterioles. A precapillary sphincter functions as a valve that controls blood flow to the tissues at the arterial end of a capillary.

Capillaries exchange nutrients and metabolic end-products between blood vessels and cells. This exchange is aided by 1-micron-thick walls, extensive branching, and massive surface area. Capillary distribution is densest where tissue activity is highest.

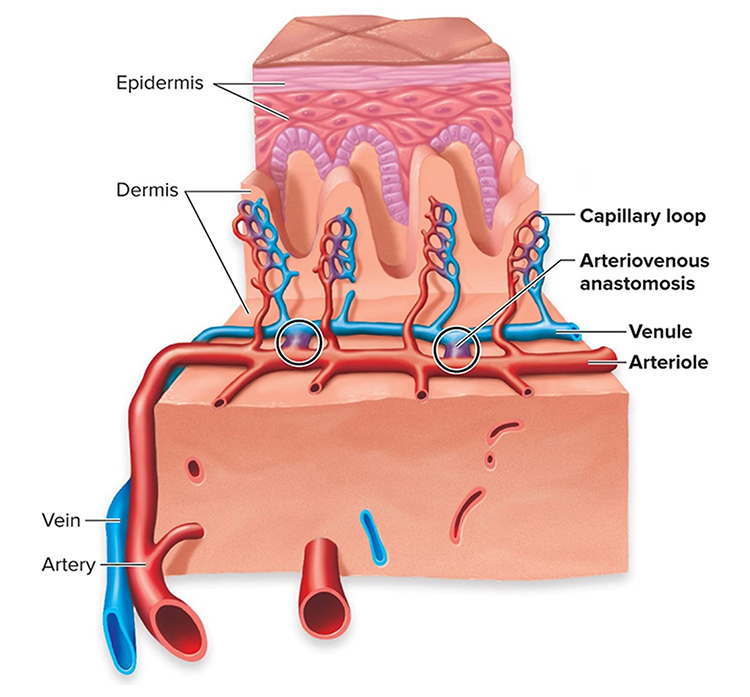

Arteriovenous Anastomoses (AVAs)

Arteriovenous anastomoses (AVAs) are junctions of two or more vessels that supply the same region.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Arteriovenous Anastomoses (AVAs) © BioSource Software LLC.

AVAs bypass capillaries, directly shunt blood from arterioles to venules, and help regulate temperature (Walløe, 2016).

These vessels contain the three layers seen in both arterioles and venules. Smooth muscle allows anastomoses to adjust diameter actively. Graphic © McGraw-Hill.

AVAs are all closed when a naked human body is exposed to temperatures around 79 degrees F. They all open as the temperature approaches 97 degrees F. AVA dilation transfers blood from the epidermis to the interior, cooling the skin. This mechanism is implicated in both Raynaud’s disease and Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure is the force exerted by blood as it presses against blood vessels. In clinical practice, BP refers to the pressure in arteries. Cardiac output is the amount of blood pumped by the heart in a minute calculated by multiplying stroke volume by heart rate. A typical value for a resting adult is 5.25 liters/minute (70 milliliters x 75 beats/minute). Stroke volume is the amount of blood ejected by the left ventricle during one contraction. Heart rate is the number of contractions per minute.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Cardiac Measurements © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © Nerthuz/ Shutterstock.com.

.jpg)

Blood leaving the left ventricle meets resistance or friction due to blood viscosity (thickness), blood vessel length, and blood vessel radius. Blood pressure equals cardiac output times resistance. Self-regulation skills that lower BP reduce cardiac output, resistance, or both.

Clinicians measure both systolic and diastolic BPs. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) is the force exerted by blood on arterial walls during contraction of the left ventricle (called systole). SBP is the upper value when BP is reported and is about 120 mmHg in young adult males (under resting conditions). Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) is the force applied against arteries during ventricular relaxation (called diastole). DBP is the lower value and is about 80 mmHg (under resting conditions). Check out the Nucleus Medical Media video on Health Journey Support Understanding Basic Blood Pressure Control.

The Heart

The heart is a hollow muscular organ about the size of a closed fist that pumps1,500 to 2,000 gallons of blood each day in the adult cardiovascular system.

Listen to a mini-lecture on an Overview of the Heart © BioSource Software LLC. The illustration below depicts blood flow © MSSA/Shutterstock.com.

Check out the Nucleus Medical Media video Normal Anatomy of the Heart at Health Journey Support.

Review the External Structure of the Heart

Click on the Quizlet logo to review an interactive diagram created by raymondmitchelafrica.

The heart beats around 100,000 times a day and 2.5 billion times during a typical lifetime. The heart contains four chambers, two atria and two ventricles. The atria are upper chambers that receive returning venous blood. The ventricles are located below the atria and pump blood from the heart into the arteries (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). Check out the Blausen Overview of Heart Anatomy and Physiology animation. Graphic © Alila Medical Media/Shutterstock.com.

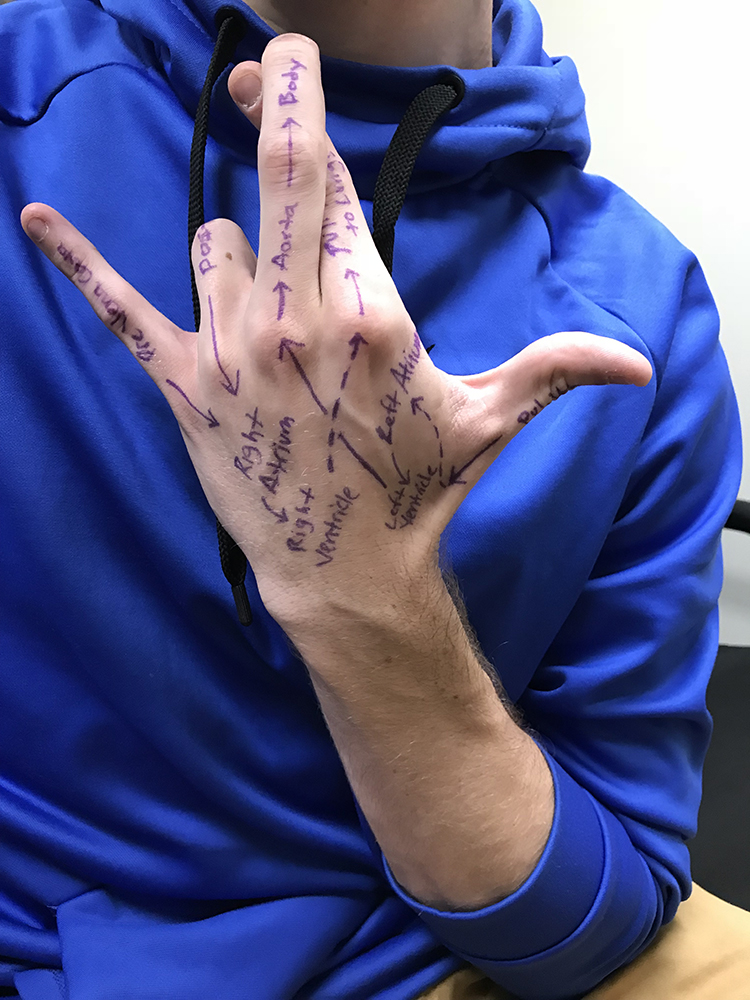

You can label the heart's arteries, chambers, and valves on the back of your hand and then place it over your chest to display the relative positions of these structures. Graphic © Zachary White.

Deoxygenated blood enters the right atrium through the superior and inferior vena cava. After passing through the right atrioventricular orifice (tricuspid valve), blood flows into the right ventricle and is pumped via the lungs' pulmonary arteries. There, wastes are removed, and oxygen is replaced. Oxygenated blood returns through pulmonary veins to the left atrium. It passes through the left atrioventricular orifice (mitral valve) and into the left ventricle. During contraction, blood is ejected through the aorta to the arterial system (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). Animation © decade3d - custom anatomy/Shutterstock.com.

The Cardiac Cycle

The cardiac cycle consists of systole (ventricular contraction, and diastole (ventricular relaxation). During systole (about 0.3 seconds), BP peaks as left ventricle contraction ejects blood from the heart. Systolic BP is measured here. During diastole (about 0.4 seconds), BP is lowest as the left ventricle relaxes. Diastolic BP is measured at this time (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). Graphic © udaix/Shutterstock.com.Pacemakers

The heart contains autorhythmic fibers that spontaneously generate the pacemaker potentials that initiate cardiac contractions.Listen to a mini-lecture on Cardiac Conduction © BioSource Software LLC.

These fibers continue to initiate heartbeats after surgeons sever all cardiac nerves and remove a heart from the chest cavity for transplantation. Autorhythmic fibers function as pacemakers and provide a conduction pathway for pacemaker potentials.

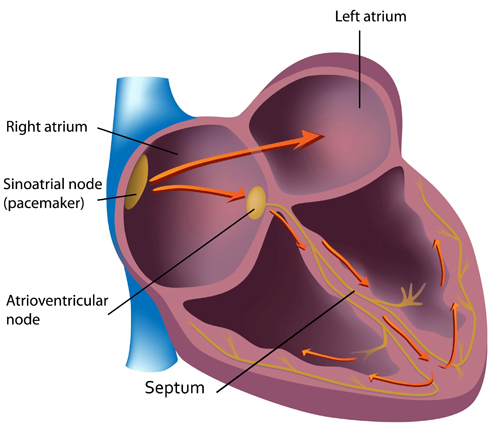

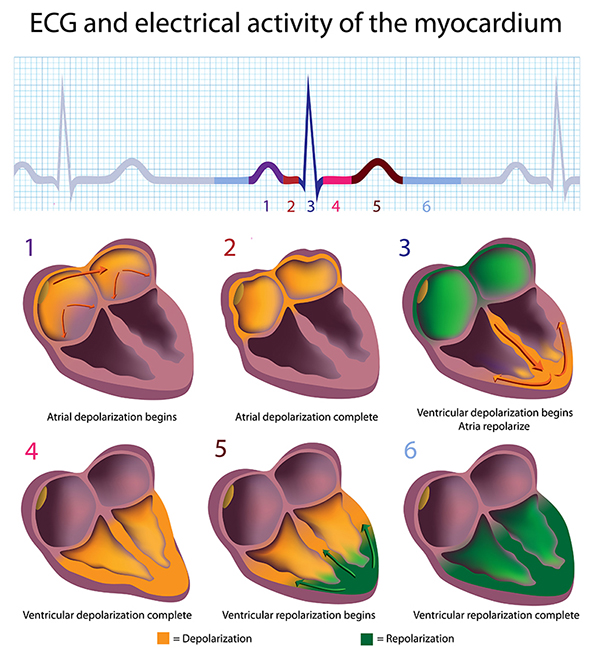

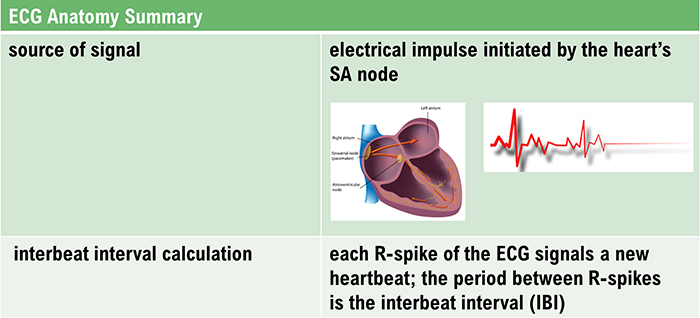

The sinoatrial (SA) node and atrioventricular (AV) node are the two internal pacemakers responsible for the heart rhythm. The electrocardiogram (ECG) records the electrical conduction system's activity (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). Check out the Blausen Conduction System animation. Graphic © Alila Medical Media/Shutterstock.com.

Cardiac Conduction

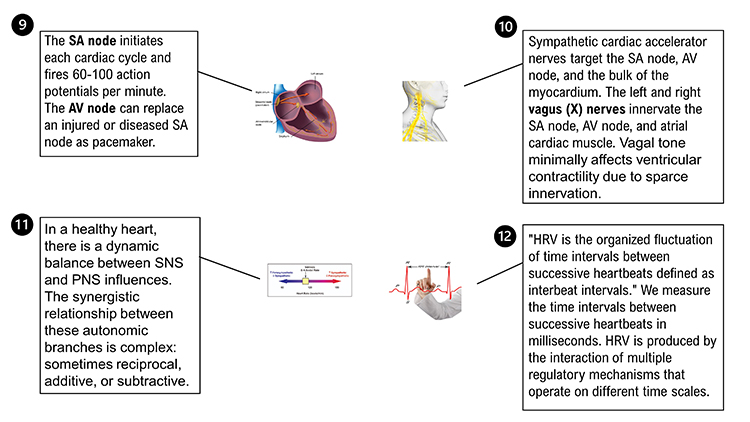

In a healthy heart, the SA node initiates each cardiac cycle by spontaneously depolarizing its autorhythmic fibers. The SA node's firing of 60-100 action potentials per minute usually prevents slower parts of the conduction system and myocardium (heart muscle) from generating competing potentials.The SA node fires an impulse that travels through the atria to the AV node in about 0.03 seconds and causes the AV node to fire. The P wave of the ECG is produced as contractile fibers in the atria depolarize. The P wave culminates in the contraction of the atria (atrial systole). Animation © 2010 Scholarpedia.

The AV node can replace an injured

or diseased SA node as a pacemaker and spontaneously depolarizes 40-60

times per minute. The signal rapidly spreads through the atrioventricular (AV)

bundle reaching the top of the septum. Descending right and left bundle

branches conduct the action potential over the ventricles

about 0.2 seconds after the appearance of the P wave.

Conduction myofibers extend from the bundle

branches into the myocardium, depolarizing contractile fibers in the

ventricles (lower chambers). Ventricular depolarization generates the

QRS complex. The ventricles contract (ventricular systole)

soon after the emergence of the QRS complex. Their contraction continues through

the S-T segment. Ventricular contractile fiber depolarization generates the

T wave about 0.4 seconds following the P wave. The ventricles

relax (ventricular diastole) 0.6 seconds after the P wave begins (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Check out the YouTube video 15 Second EKG. Graphic ©

Alila Medical Media/Shutterstock.com.

Considerations for HRV Biofeedback Training

Clinicians should examine ECG morphology for evidence of arrhythmias, ischemia, and prolonged Q-T intervals that could endanger client safety as part of assessment for HRV biofeedback training (Drew et al., 2004).Regulation by the Cardiovascular Center

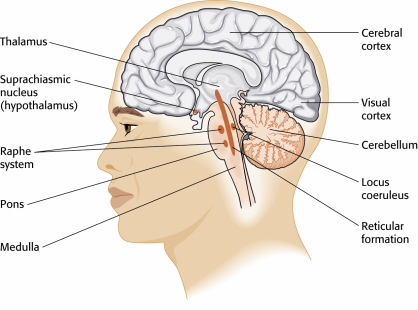

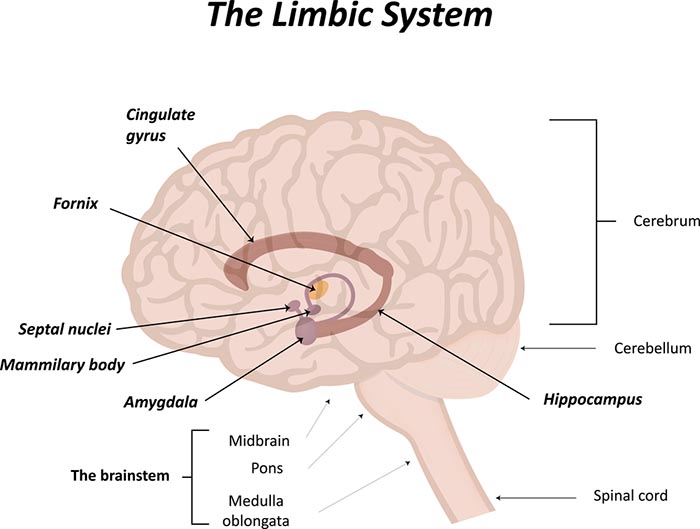

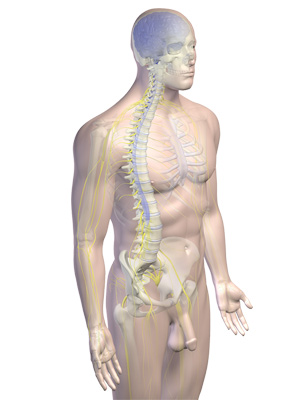

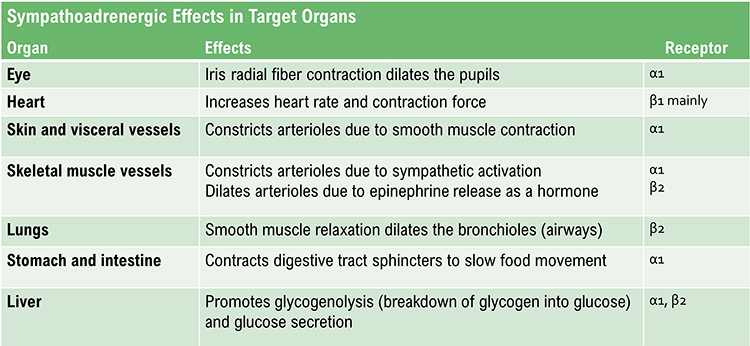

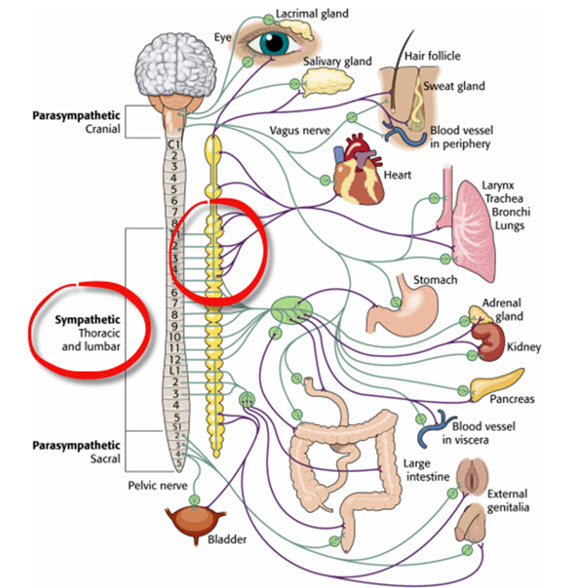

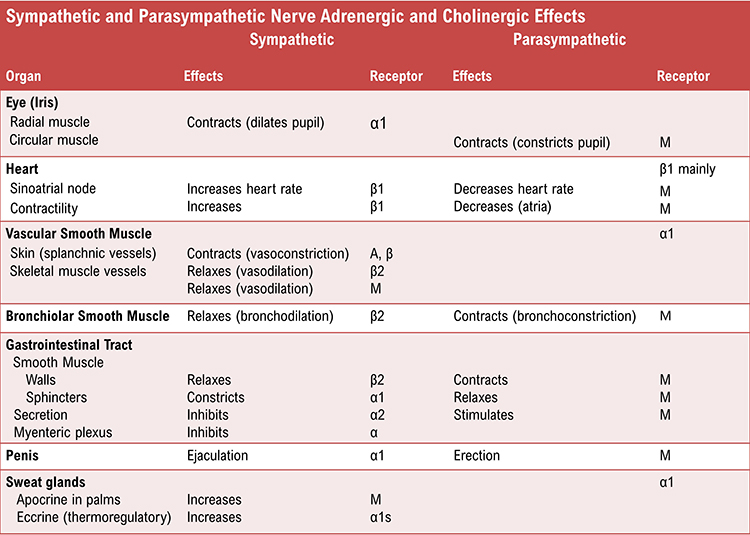

While the SA node generates the normal heartbeat cardiac rhythm, autonomic motor neurons and circulating hormones and ions influence the interbeat interval (time between adjacent heartbeats) and the myocardial contraction force. The cardiovascular center, located in the medulla of the brainstem, integrates sensory information from proprioceptors (limb position), chemoreceptors (blood chemistry), and baroreceptors (BP) as well as information from the cerebral cortex and limbic system. The cardiovascular center responds to sensory and higher brain center input by adjusting autonomic balance via sympathetic and parasympathetic motor neurons (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).Sympathetic Control

Sympathetic cardiac accelerator nerves target the SA node, AV node, and the bulk of the myocardium (heart muscle). Action potentials conducted by these motor neurons release NE and E. These neurotransmitters bind to beta-adrenergic (β1) receptors located on cardiac muscle fibers. This speeds spontaneous SA and AV node depolarization (increasing HR) and strengthens the atria and ventricles' contractility.In failing hearts, the number of beta-adrenergic receptors is reduced, and their cardiac muscle contraction in response to NE and E binding is weakened (Ogletree-Hughes et al., 2001).

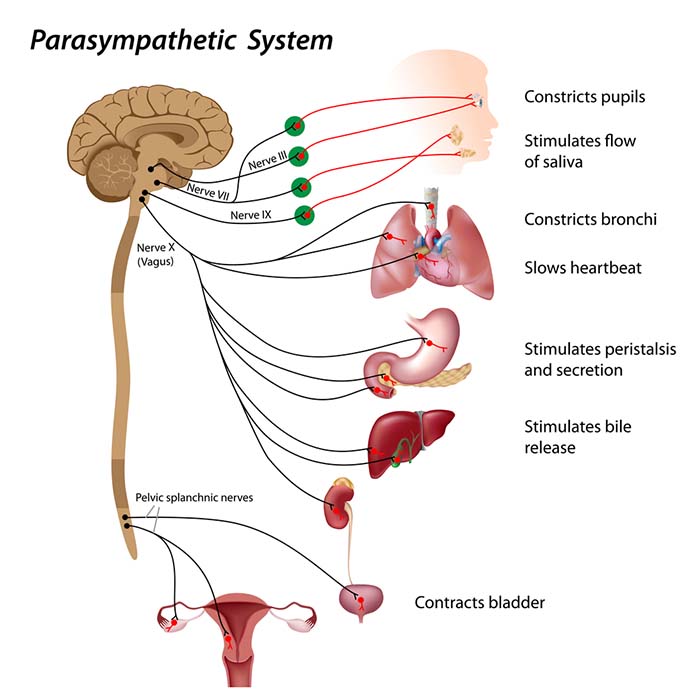

Parasympathetic Control

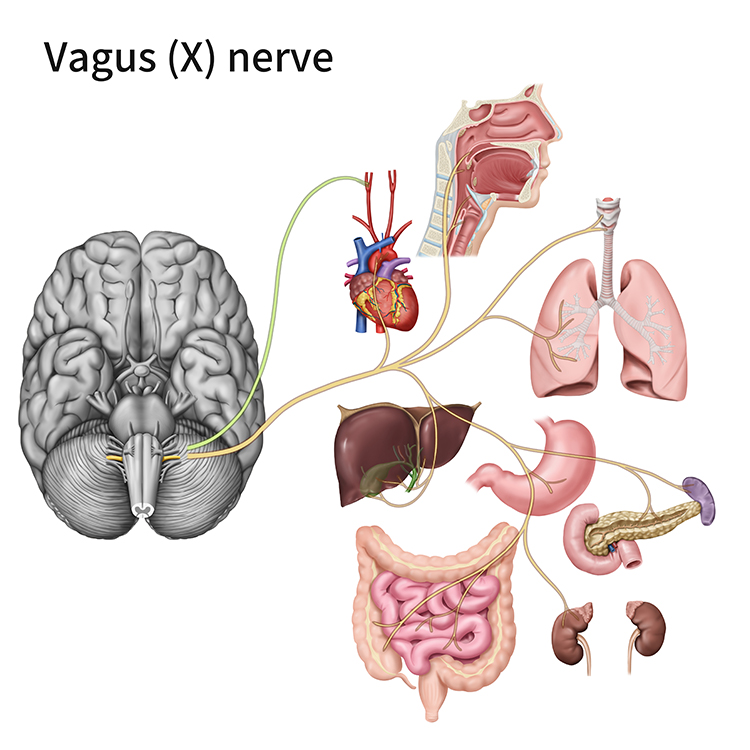

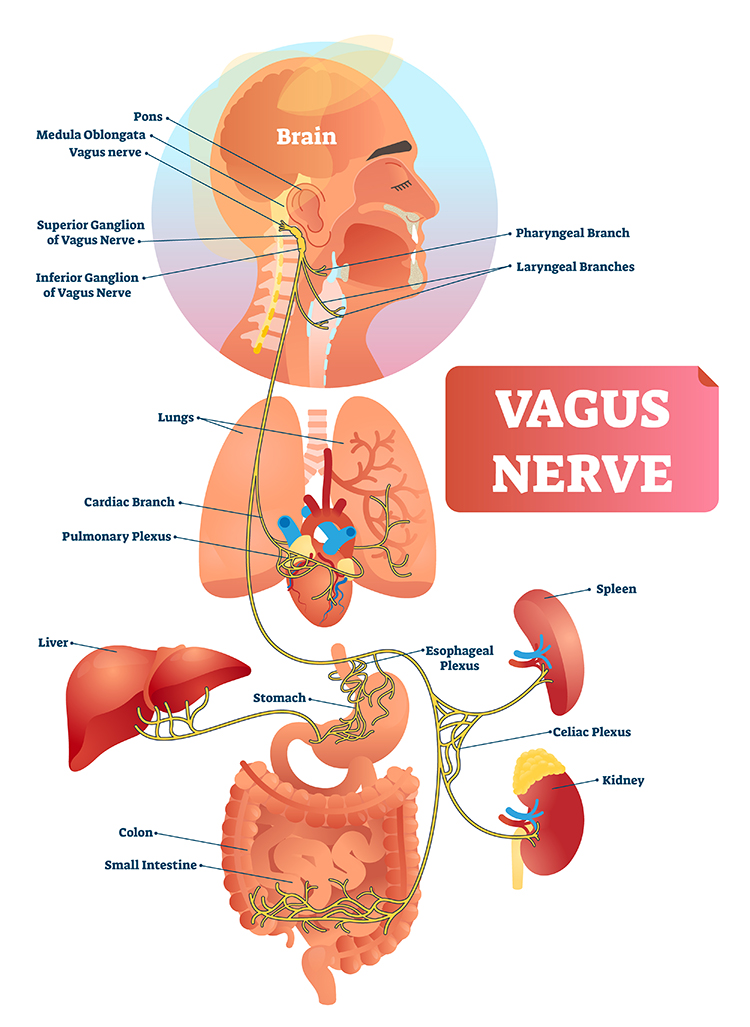

Like cardiac accelerator nerves, the left and right parasympathetic vagus (X) nerves also innervate the SA node, AV node, and atrial cardiac muscle.Listen to a mini-lecture on Autonomic Control of the Heart © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © SciePro/Shutterstock.com.

Caption: Vagus Nerve

Firing by these motor neurons triggers acetylcholine release and binding to muscarinic (mainly M2) receptors. Cholinergic binding decreases the rate of spontaneous depolarization in the SA and AV nodes (slowing heart rate). Since there is sparse vagal innervation of the ventricles, vagal tone minimally affects the ventricular contractility (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

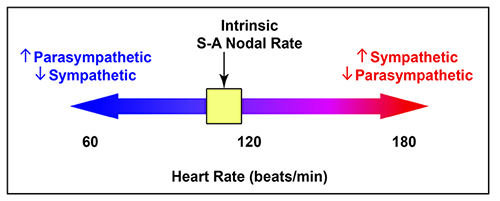

Autonomic Balance

There is a dynamic balance between sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) influences in a healthy heart. The synergistic relationship between these autonomic branches is complex: sometimes reciprocal, additive, or subtractive (Gevirtz, Schwartz, & Lehrer, 2016).PNS control predominates at rest, resulting in an average HR of 75 beats per minute (bpm) that is significantly slower than the SA node's intrinsic rate, which decreases with age, from an average 107 bpm at 20 years to 90 bpm at 50 years (Opthof, 2000).

The PNS can slow the heart by 20 or 30 beats per minute or briefly stop it (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). This control illustrates the response called accentuated antagonism (Olshansky et al., 2011). Parasympathetic nerves exert their effects more rapidly (< 1 second) than sympathetic nerves (> 5 seconds) (Nunan et al., 2010; Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014; Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

While the SNS can suppress PNS activity, it can also increase PNS reactivity (Gellhorn, 1957). Parasympathetic rebound may occur following high stress levels, resulting in increased nighttime gastric activity (Nada et al., 2001) and asthma symptoms (Ballard, 1999).

Cardiac Regulation by Hormones and Ions

Circulating hormones and ions also influence the heart. Epinephrine, norepinephrine, and thyroid hormones increase HR and contractibility. The cations (positive ions) K+, Ca2+, and Na+ significantly affect cardiac function. While elevated plasma levels of K+ and Na+ decrease HR and contraction force, high intracellular Ca2+ levels have the opposite effect (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).Heart Rate

Heart rate (also called stroke rate) is the number of heartbeats per minute. This value is 75 beats/minute for a resting young adult male. Resting rates slower than 60 beats/minute (bradycardia) and faster than 100 beats/minute (tachycardia) may indicate a cardiovascular disorder. Typical non-athlete HRs are 60-80 bpm. Athletes may have HRs between 40-60 bpm (Khazan, 2019).

Abnormal or irregular rhythms are called arrhythmias or dysrhythmias (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Heart rate is significant because a high rate can reduce heart rate variability. Faster HRs allow less time between successive heartbeats for HR to vary. This lowers HRV.

Analysis of HRs in healthy individuals reveals a chaotic pattern. Heart rate values are not constant but are unpredictable due to multiple hormonal and neural control systems. Successive values might be 65, 78, 72, 86, illustrating the variability of a healthy heart that can rapidly adapt to changing workloads. Variability is severely reduced in hearts damaged by cardiovascular disease.

Below is a three-dimensional BioGraph ® Infiniti heart rate variability (HRV) display of the ECG power spectrum. HRV biofeedback training aims at increasing the power at 0.1 Hz (6 breaths per minute) to maximize healthy variability.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

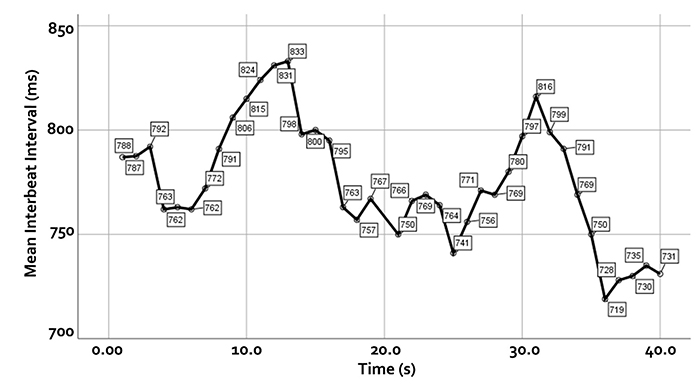

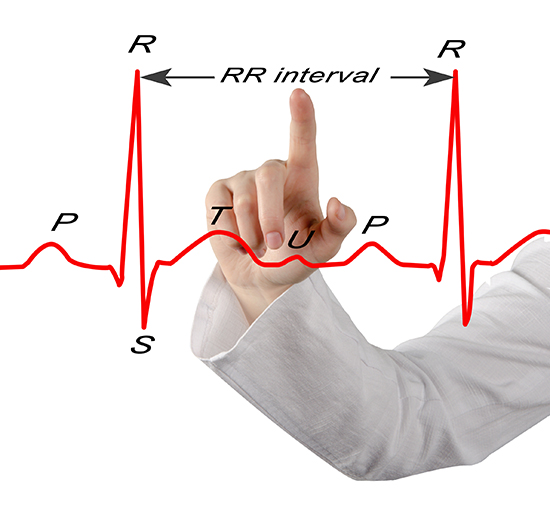

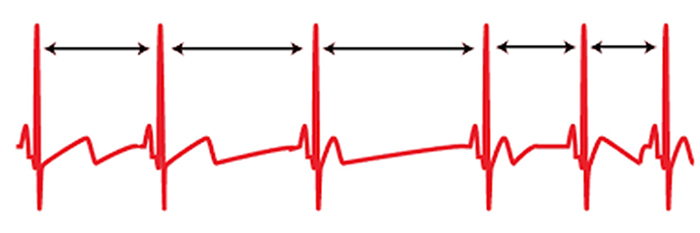

Heart rate variability (HRV) consists of changes in the time intervals between consecutive heartbeats (Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology, 1996).Listen to a mini-lecture on a Heart Rate Variability Overview © BioSource Software LLC.

"HRV is the organized fluctuation of time intervals between successive heartbeats defined as interbeat intervals" (Shaffer, Meehan, & Zerr, 2020).

We measure the time intervals between successive heartbeats in milliseconds. Graphic courtesy of Dick Gevirtz.

HRV is produced by interacting regulatory mechanisms that operate on different time scales (Moss, 2004). Circadian rhythms, core body temperature, and metabolism contribute to 24-hour HRV recordings, representing the "gold standard" for clinical HRV assessment. The parasympathetic, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems produce short-term (e.g., 5-minute) HRV measurements. Graphic © arka38/Shutterstock.com.

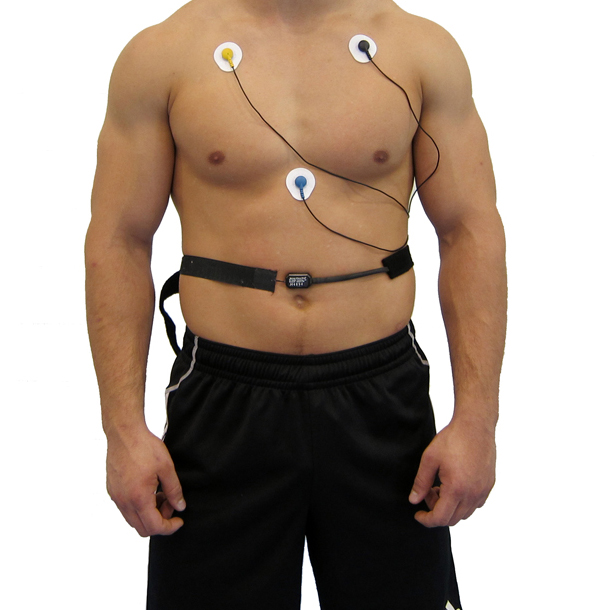

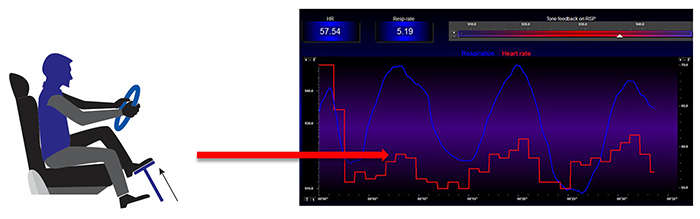

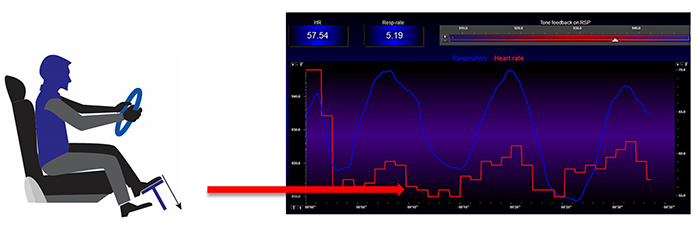

Clinicians can monitor HRV using ECG and respiration sensors, as shown below.

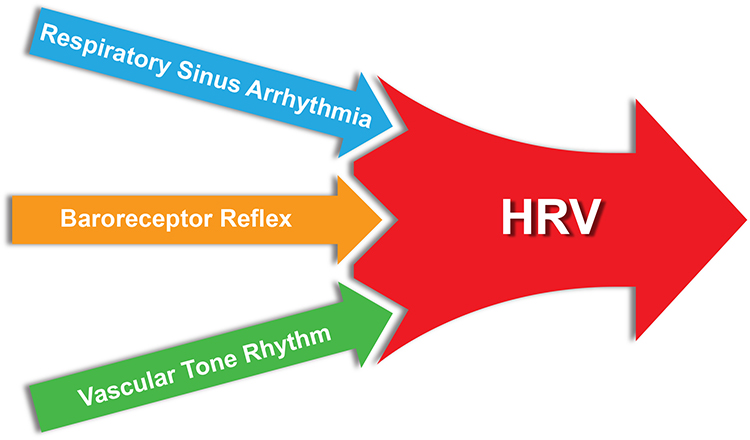

Sources of Heart Rate Variability

Respiratory sinus arrhythmia and the baroreflex are the first and second most important sources of HRV, respectively (Hayano & Yuda, 2019).Listen to a mini-lecture on Sources of Heart Rate Variability © BioSource Software LLC.

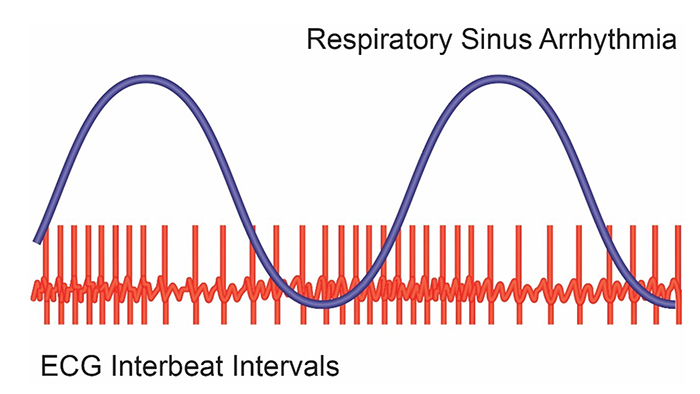

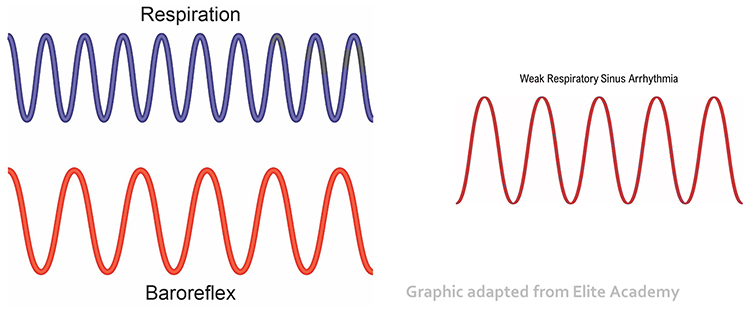

Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), heart rate speeding and slowing across each breathing cycle, is the primary and entirely parasympathetic source of HRV (Gevirtz, 2020). Graphic adapted from Elite Academy.

Inhalation partially disengages the vagal brake, speeding heart rate. This is purely parasympathetic. Graphics inspired by Dick Gevirtz.

Exhalation reapplies the vagal brake, slowing heart rate.

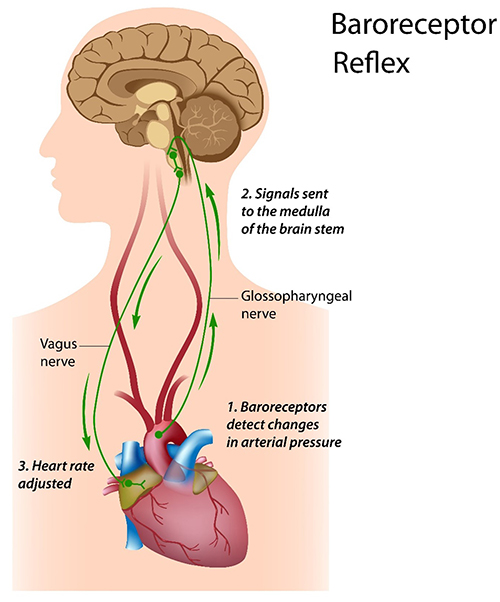

The baroreceptor reflex, which exerts homeostatic control over acute BP changes, is the second-most-important and entirely parasympathetic source of HRV (Gevirtz, 2020).

Listen to a mini-lecture on the Baroreceptor Reflex © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © Alila Sai Mai/Shutterstock.com.

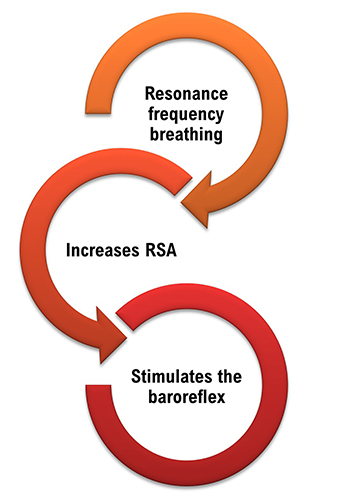

Slow-paced breathing increases RSA by stimulating the baroreceptor system at its unique resonance frequency (~ 0.1 Hz). The resonance frequency is caused by the delay in the baroreflex (Lehrer et al., 2004). Before HRVB, respiration and the baroreflex are usually out of phase resulting in weak resonance effects.

Visualize pushing a child on a swing. There is a single frequency that pushes the child the highest. The best pushing rate is analogous to the resonance frequency (Khazan, 2020). Graphic © Billion Photos/Shutterstock.com.

Resonance is simple physics (Lehrer, 2020). The baroreflex system exhibits resonance since it is a feedback system with a fixed delay. Inertia due to blood volume in the vascular tree accounts for most of this delay.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Resonance © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © Shot4Sell/Shutterstock.com.

Taller people and men have lower resonance frequencies than women and shorter people because the former have larger blood volumes.

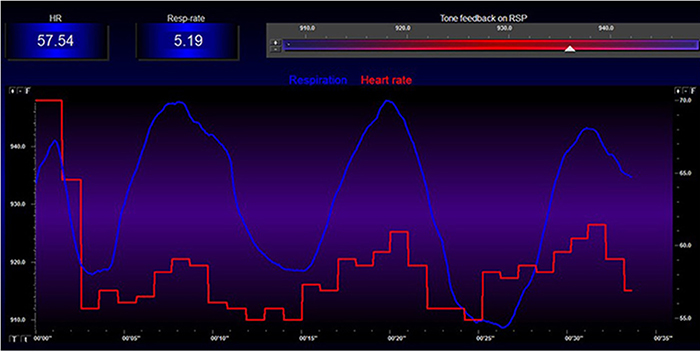

When clients breathe at their resonance frequency, heart rate and respiration are in perfect phase (0°); their peaks and valleys coincide.

Listen to a mini-lecture on the Resonance Frequency © BioSource Software LLC.

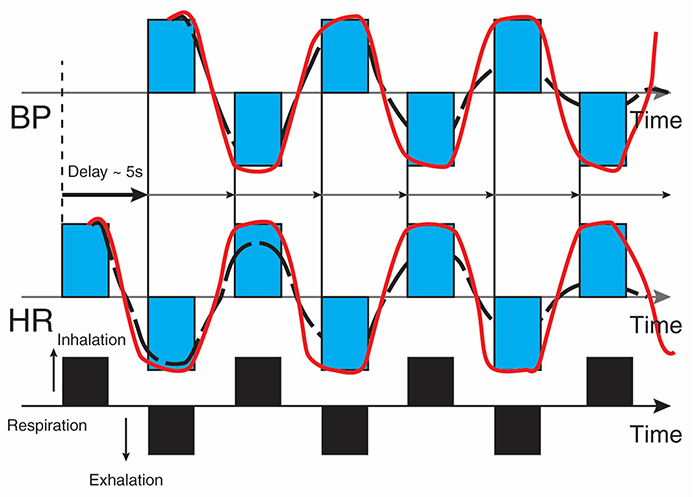

Resonance frequency breathing also modulates BP changes since HR and BP oscillations are 180° out of phase (DeBoer, Karemaker, & Strackee, 1987; Vaschillo et al., 2002). Graphic adapted from Evgeny Vaschillo.

Caption: The bottom line represents respiration. A rising black bar is inhalation, and a falling black bar means exhalation. The next lines represent HR and BP. This diagram allows us to see the changes in HR and BP produced by breathing. Starting at the bottom left, inhalation speeds the heart and about 5 seconds later, BP falls. During exhalation, the heart slows, and about 5 seconds later, BP increases.

Before HRVB, respiration and the baroreflex are usually out of phase resulting in weak resonance effects. Graphic adapted from Elite Academy.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Resonance Frequency Breathing © BioSource Software LLC.

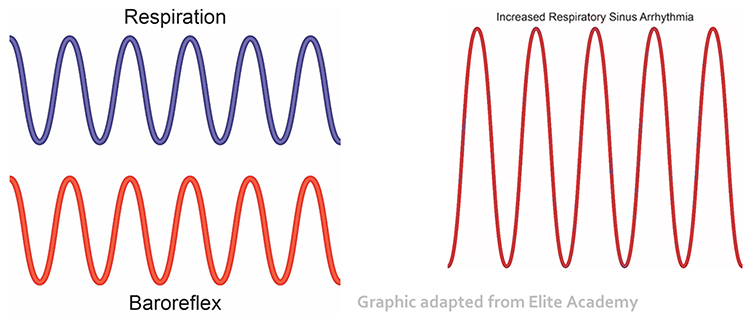

HRV biofeedback training slows breathing to the baroreflex’s rhythm, which aligns these processes and significantly increases resonance effects. Graphic adapted from Elite Academy.

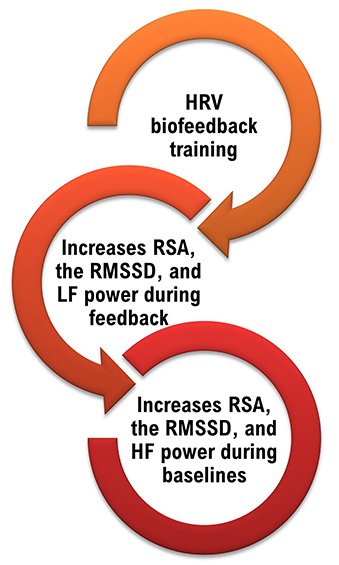

Slowing breathing to rates between 4.5-6.5 bpm for adults and 6.5-9.5 bpm for children increases RSA (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014). Increased RSA immediately “exercises” the baroreflex without changing vagal tone or tightening BP regulation. Those changes require weeks of practice. HRV biofeedback can increase RSA 4-10 times compared to a resting baseline (Lehrer et al., 2020b; Vaschillo et al., 2002).

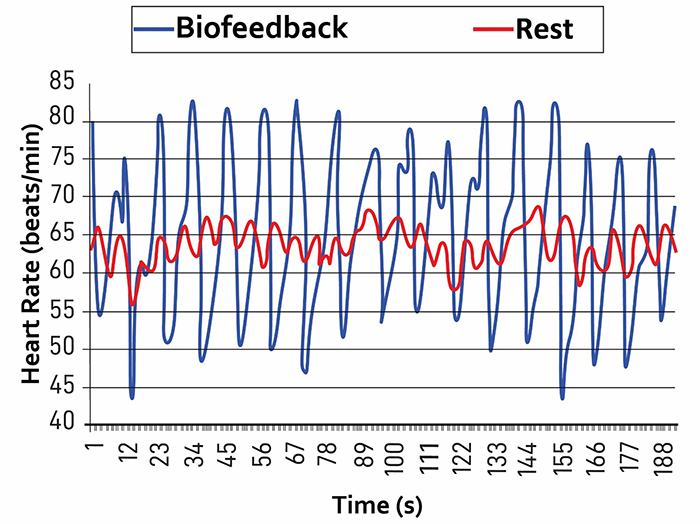

Listen to a mini-lecture on Increased Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic adapted from Gevirtz et al., 2016).

Caption: The red waveform shows HR oscillations while resting without breathing instructions or feedback. The blue waveform shows HR oscillations with HRV biofeedback and breathing from 4.5-6.5 bpm.

Listen to a mini-lecture on HRV Changes During and After Training © BioSource Software LLC.

You can observe the effect of a breathing rate on RSA during paced breathing and select the rate that produces the largest HR oscillations. Adult breathing from 4.5-6.5 bpm shifts the ECG peak frequency from the high-frequency band (~0.20 Hz) to the cardiovascular system’s resonance frequency (~0.10 Hz). This more than doubles the energy in the low-frequency band of the ECG (0.04-0.15 Hz).

We train clients to increase low-frequency power and RSA so that high-frequency power and time-domain measures like the RMSSD will increase during baselines when breathing at typical rates (Lehrer, 2020).

Why Is Heart Rate Variability Important?

A healthy heart is not a metronome. When the time intervals between heartbeats significantly change across successive breathing cycles, this shows that the cardiovascular center can effectively modulate vagal tone.Listen to a mini-lecture on Why Is Heart Rate Variability Important? © BioSource Software LLC.

The record below shows healthy variability. The time intervals between successive heartbeats differ.

"The complexity of a healthy heart rhythm is critical to the maintenance of homeostasis because it provides the flexibility to cope with an uncertain and changing environment...HRV metrics are important because they are associated with regulatory capacity, health, and performance and can predict morbidity and mortality" (Shaffer, Meehan, & Zerr, 2020).

Check out the YouTube video HRV Training and its Importance. Graphic © Axynia/Shutterstock.com.

"... HRV is associated with executive function, regulatory capacity, and health... Cardiac vagal control indexes how efficiently we mobilize and utilize limited self-regulatory resources during resting, reactivity, and recovery conditions" (Shaffer, Meehan, & Zerr, 2020).

Vagal tone modulation helps maintain the dynamic autonomic balance critical to cardiovascular health. Autonomic imbalance due to deficient vagal inhibition is implicated in increased morbidity and all-cause mortality (Thayer, Yamamoto, & Brosschot, 2010).Heart Rate Variability Is a Marker for Disease and Adaptability

Since a healthy cardiovascular system integrates multiple control systems, its overlapping oscillatory patterns are chaotic.Listen to a mini-lecture on Heart Rate Variability Is a Marker for Disease and Adaptability © BioSource Software LLC.

The double compound pendulum animation from Wikipedia shown below illustrates chaotic behavior. Slightly changing the pendulum's starting condition results in a radically different trajectory.

A healthy heart exhibits complexity in its oscillations and rapidly adjusts to sudden physical and psychological challenges due to its effective interlocking cardiac control systems. A healthy heart illustrates the concept of allostasis or the achievement of stability through change. In contrast, an aging or diseased heart shows noncomplex oscillations and ineffectively responds to sudden demands due to the breakdown of its control mechanisms (Lehrer & Eddie, 2013). Check out the YouTube video Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Biofeedback by Mark Stern.

HRV appears to index autonomic functioning, BP, neurocardiac functioning, digestion, oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange, vascular tone (diameter of resistance vessels), and possibly facial muscle regulation (Gevirtz et al., 2016). HRV reflects the vagal contribution to executive functions, affective control, and social self-regulation (Byrd et al., 2015; Laborde et al., 2017; Mather & Thayer, 2018).

Vagal tank theory (Laborde et al., 2018) argues that vagal traffic to the heart indicates how efficiently we mobilize and use scarce self-regulatory resources.

Heart rate variability biofeedback is extensively used to treat various disorders (e.g., asthma and depression) and enhance performance in various contexts (e.g., sports; Gevirtz, 2013; Lehrer et al., 2020a; Tan et al., 2016).

Lehrer et al. (2020) observed that “…HRVB has the largest effect sizes on anxiety, depression, anger, and athletic/artistic performance and the smallest effect sizes on PTSD, sleep, and quality of life” (p. 109).

Although the final targets of these applications may differ, HRVB increases vagal tone (Vaschillo et al., 2006) and stimulates the negative feedback loops responsible for homeostasis (Lehrer & Eddy, 2013).

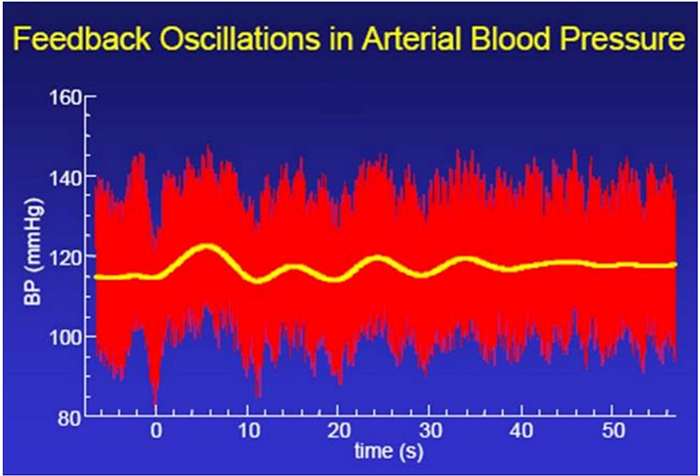

Whereas HRV is desirable, BP variability can endanger health. We require BP stability under constant workloads (Gevirtz, 2020). Graphic courtesy of Dick Gevirtz.

Reduced HRV Is Associated with Disease and Loss of Adaptability

In the early 1960s, researchers found that changes in HRV preceded fetal distress (Hon & Lee, 1963).Listen to a mini-lecture on Reduced HRV Is Associated with Disease and Loss of Adaptability © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © SciePro/Shutterstock.com.

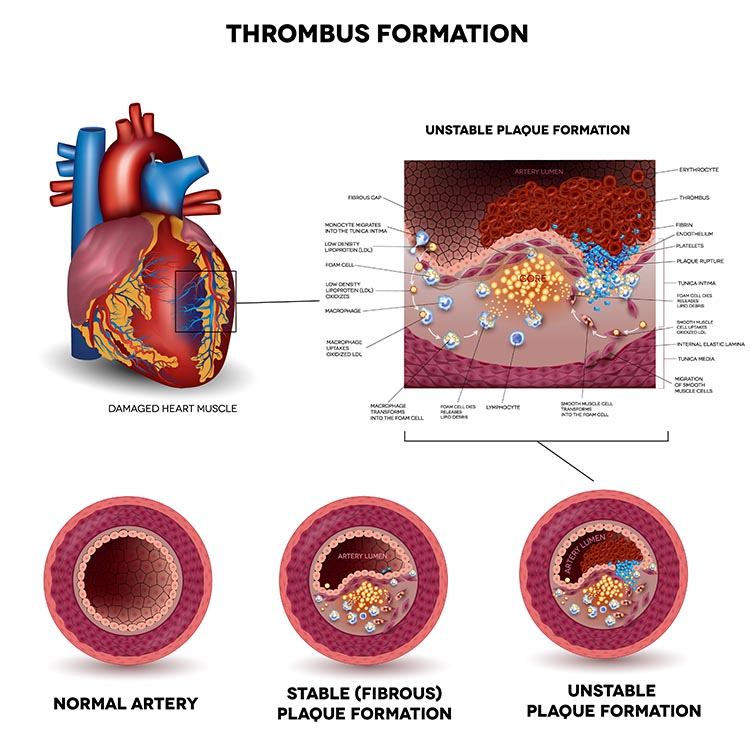

Reduced HRV is associated with vulnerability to physical and psychological stressors and disease (Lehrer, 2007). Prospective studies have shown that decreased HRV is the strongest independent predictor for the progression of coronary atherosclerosis (McCraty & Shaffer, 2015).

Low HRV is a marker for cardiovascular disorders, including hypertension, especially with left ventricular hypertrophy; ventricular arrhythmia; chronic heart failure; and ischemic heart disease (Bigger et al., 1995; Casolo et al., 1989; Maver, Strucl, & Accetto, 2004; Nolan et al., 1992; Roach et al., 2004). Low HRV predicts sudden cardiac death, especially due to arrhythmia following myocardial infarction and post-heart attack survival (Bigger et al., 1993; Bigger et al., 1992; Kleiger et al., 1987).

Depression in myocardial infarction (MI) patients increases mortality. Depressed patients are twice as likely as non-depressed individuals to have lower HRV (16% vs. 7%). Lower HRV is a strong independent predictor of post-MI death (Craney et al., 2001). HRVB might reduce anxiety and depression, which are associated with low vagal activity, because it increases vagal tone. From Friedman’s (2007) perspective, the problem is not “a sticky accelerator.” HRVB may fix “bad brakes” (p. 186).

Reduced HRV may predict disease and mortality because it indexes reduced regulatory capacity, which is the ability to surmount challenges like exercise and stressors adaptively. Patient age may be an essential link between reduced HRV and regulatory capacity since both HRV and nervous system function decline with age (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).

Reduced HRV is also seen in disorders with autonomic dysregulation, including anxiety and depressive disorders, asthma, and vulnerability to sudden infant death (Agelink et al., 2002; Carney et al., 2001; Cohen & Benjamin, 2006; Giardino, Chan, & Borson, 2004; Kazuma, Otsuka, Matsuoka, & Murata, 1997). Lehrer (2007) believes that HRV indexes adaptability and marshals evidence that increased RSA represents more efficient regulation of BP, HR, and gas exchange by synergistic control systems.

Heart-Brain Interactions

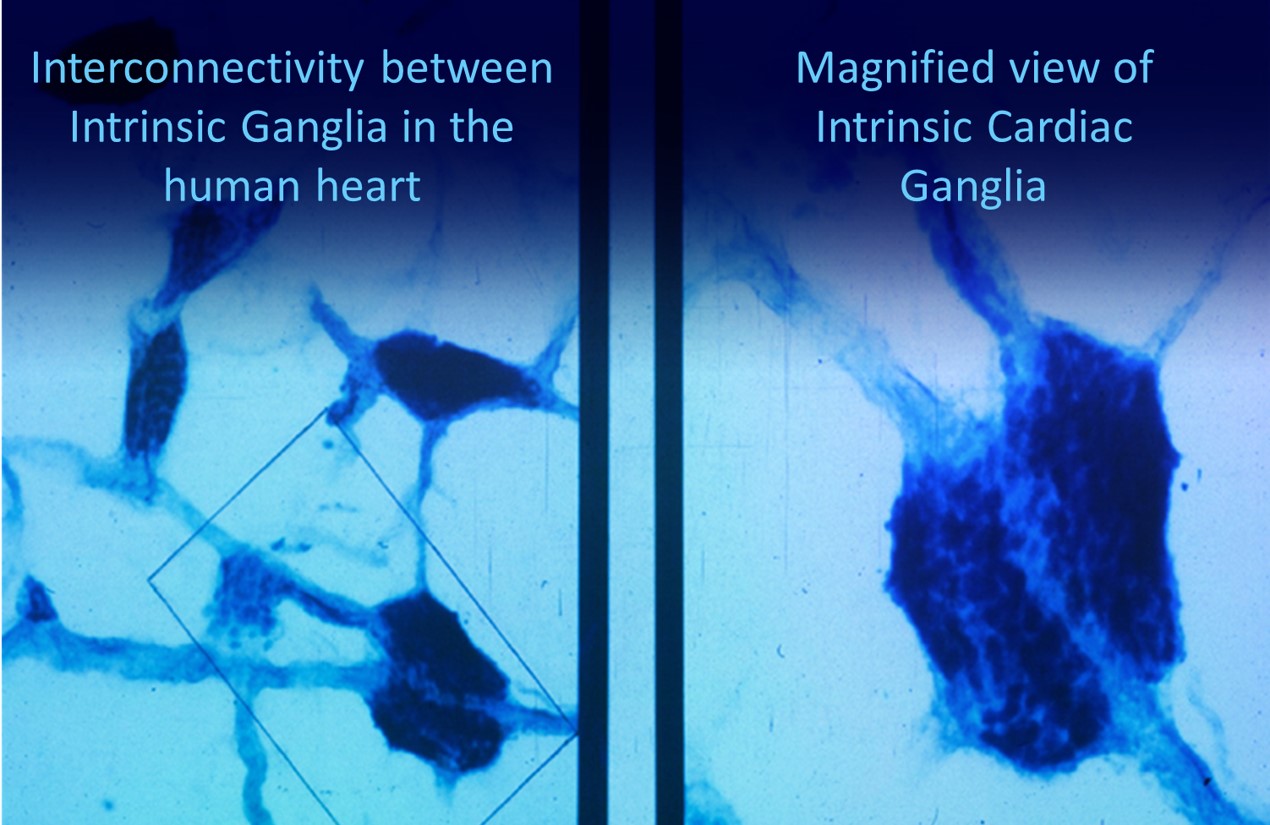

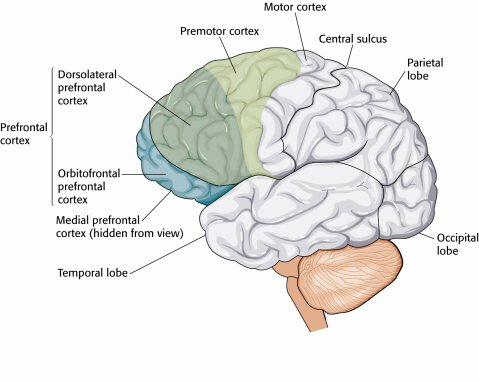

Thayer and Lane (2000) outline a neurovisceral integration model that describes how a central autonomic network (CAN) links the brainstem NST with forebrain structures (including the anterior cingulate, insula, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hypothalamus) through feedback and feed-forward loops. They speculate that a breakdown in negative feedback may produce the increased SNS arousal that characterizes anxiety disorders. Thayer et al. (2012, p. 754) contend that regions that include the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex, which evaluate "threat and safety," help regulate HRV through their connections with the NST.Shaffer, McCraty, and Zerr (2014) propose that interconnected cardiac ganglia create an intrinsic nervous system within the heart that influences the S-A and A-V node pacemakers and forms reciprocal connections with the extrinsic cardiac ganglia found in the chest cavity and the medulla. The sensory, interconnecting, afferent, and motor neurons within the heart can function independently and constitute a "little brain" on the mammalian heart.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Heart-Brain Interactions © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © Naeblys/ Shutterstock.com.

The ascending afferent nerves help to regulate the heart and its rhythms physiologically and influence efferent SNS and PNS activity. From 85-90% of vagus nerve fibers are afferents, and more afferents from the heart target the brain than any other major organ.

Afferent signals from the intrinsic cardiac nervous system appear to affect attention, motivation, perceptual sensitivity, and emotional processing (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014). Graphic © 2012 Institute of HeartMath.

MacKinnon, Gevirtz, McCraty, and Brown (2013) reported that HRV influences the amplitude of heartbeat event-related potentials (HERPs). The amplitude of these negative EEG potentials that appear about 200-300 ms after each R-spike indexes cardiac afferent communication with the brain. Both negative and positive emotion conditions reduced HRV and HERP amplitude. In contrast, resonance frequency breathing increased HRV above baseline and increased HERP amplitude.

The authors speculated that resonance frequency breathing reduces interference with vagal afferent signal transmission from the heart to the cerebral cortex.

The following intrinsic ganglia images © 2012 Dr. Andrew Armour and the Institute of HeartMath.

Glossary

0.1 Hz biofeedback: training to concentrate ECG power around 0.1 Hz in the low frequency (LF) band by teaching patients to breathe diaphragmatically at their resonance frequency around 6 breaths per minute and experience positive emotional tone to maximize HR variability.

alpha-adrenergic receptors: G protein-coupled receptors for the catecholamines epinephrine and norepinephrine. The binding of these catecholamines to arteriole alpha-adrenergic receptors can produce hand-cooling.

arrhythmias: abnormal or irregular rhythms, also called dysrhythmias.

arteries: blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart and that are divided into elastic and muscular arteries and arterioles.

arteriole vasoconstriction: the decreased diameter of an arteriole’s lumen due to activation of vasoconstricting sympathetic nerves that act on alpha-adrenergic receptors, circulating hormones, and local chemical factors.

arteriole vasodilation: the increased diameter of an arteriole’s lumen due to the circulation of a beta-adrenergic agent in the blood. There are no vasodilating nerves in the fingers.

arterioles: the almost-microscopic (8-50 microns in diameter) blood vessels that deliver blood to capillaries and anastomoses. Arterioles may control up to 50% of peripheral resistance through their narrow diameter, contractility, and massive surface area that follows a fractal pattern.

arteriovenous anastomoses (AVAs): junctions of two or more vessels that supply the same region, directly shunt blood from arterioles to venules, and help to regulate temperature.

atrioventricular (AV) bundle: cardiac cells that conduct electrical impulses from the AV node to the top of the septum.

atrioventricular (AV) node: one of two internal pacemakers primarily responsible for the heart rhythm, located between the atria and the ventricles.

baroreflex: baroreceptor reflex that provides negative feedback control of BP. Elevated BP activates the baroreflex to lower BP, and low BP suppresses the baroreflex to raise BP.

beta-adrenergic agent: a molecule that binds to a beta-adrenergic receptor to start the cascade that causes hand-warming.

beta-adrenergic receptors: G protein-coupled receptors for the catecholamines epinephrine and norepinephrine. Catecholamine binding to the lumen of an arteriole is responsible for hand-warming.

blood pressure: the force exerted by blood as it presses against arteries.

blood volume pulse (BVP): the phasic change in blood volume with each heartbeat. It is the vertical distance between the minimum value (trough) of one pulse wave and the maximum value (peak) of the next measured using a photoplethysmograph (PPG).

bundle branches: fibers that descend along both sides of the septum (right and left bundle branches) and conduct the action potential over the ventricles about 0.2 seconds after the appearance of the P wave.

capillaries: blood vessels that are 7-9 microns in diameter, found near almost all cells, and that may directly connect arterioles with venules or form extensive networks for rapid exchange of a large volume of substances (nutrients and waste products).

cardiac cycle: one cycle consists of systole (ventricular contraction) and diastole (ventricular relaxation).

cardiac output: the amount of blood pumped by the heart in a minute calculated by multiplying stroke volume times HR. This is 5.25 liters/minute (70 milliliters x 75 beats/minute) in a normal, resting adult.

cardiotachometer: a device that measures the frequency of ventricular contraction beat-to-beat.

cations: positive ions like K+, Ca2+, and Na+.

chaos: unpredictability due to non-linear dynamics.

conduction myofibers: fibers that extend from the bundle branches into the myocardium, depolarizing contractile fibers in the ventricles.

diastole: the period when the ventricles or atria relax.

diastolic blood pressure (DBP): the force applied against arteries during ventricular relaxation.

dilation: increased lumen diameter.

dysrhythmias: an arrhythmia.

elastic arteries: the large arteries like the aorta that distribute blood from the heart to muscular arteries.

electrocardiogram (ECG): a recording of the heart's electrical activity using an electrocardiograph.

frequency domain measures of HRV: the calculation of the absolute or relative power of the HRV signal within four frequency bands.

hand-cooling: reduced peripheral blood flow mainly controlled by vasoconstricting sympathetic nerves that act on alpha-adrenergic receptors. Circulating hormones and local factors also reduce the arteriolar diameter.

hand-warming: increased peripheral blood flow primarily due to circulating hormones and local vasodilators. There are no vasodilating nerves in the fingers, although they exist in the forearm.

heart: a hollow, muscular organ, about the size of a closed fist that contains four chambers (two ventricles and two atria) that function as two pumps.

heart rate: the number of heartbeats per minute, also called stroke rate.

heart rate variability (HRV): beat-to-beat changes in HR, including changes in the RR intervals between consecutive heartbeats.

high coherence: a single high amplitude peak in the 0.09-0.14 Hz range.

high-frequency (HF) band: the ECG frequency range from 0.15-0.40 Hz that represents the inhibition and activation of the vagus nerve by breathing (RSA).

interbeat interval (IBI): the time interval between the peaks of successive R-spikes (initial upward deflections in the QRS complex). This period is also called the NN (normal-to-normal) interval.

left atrium: the upper chamber of the heart that receives oxygenated blood from the pulmonary veins and pumps it to the left ventricle.

left ventricle: the bottom chamber of the heart that receives oxygenated blood from the left atrium and pumps it through the aorta.

low-frequency (LF) band: the ECG frequency range of 0.04-0.15 Hz that may represent the influence of PNS, SNS, and baroreflex activity (when breathing at resonance frequency).

medium-sized muscular arteries: arteries like the brachial artery that receive blood from elastic arteries and distribute blood throughout the body.

nucleus ambiguus system: the nucleus dorsal to the inferior olivary nucleus of the upper medulla that gives rise to vagus nerve motor fibers.

P wave: an ECG structure produced as contractile fibers in the atria depolarizes and culminates in the atria's contraction (atrial systole).

parasympathetic vagus (X) nerves: cranial nerves that arise from the medulla’s cardiovascular center, decrease the rate of spontaneous depolarization in SA and AV nodes, and slow the HR from the SA node's intrinsic rate of 100 beats per minute.

person effect: Taub and School's (1978) observation that biofeedback training is a social situation and that a client's relationship with the therapist may be the most critical aspect of training.

photoplethysmograph (PPG): a device that measures the relative amount of blood flow through tissue using a photoelectric transducer.

precapillary sphincter: in capillaries, a valve at the arterial end of a capillary that controls blood flow to the tissues.

pulse wave velocity (PWV): the rate of pulse wave movement through the arteries that is measured by placing pressure transducers (motion sensors) at two points along the arterial system (like the brachial and radial arteries of the same arm).

QRS complex: an ECG structure that corresponds to the depolarization of the ventricles.

Raynaud's patients: medical patients diagnosed with Raynaud’s disease or Raynaud’s phenomenon exhibit abnormal anastomoses dilation in response to mild cold-related stimuli.

regulatory capacity: the ability to adaptively respond to challenges like exercise and stressors.

respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA): respiration-driven heart rhythm that contributes to the high frequency (HF) component of HRV. Inhalation inhibits vagal nerve slowing of the heart (increasing HR), while exhalation restores vagal slowing (decreasing HR).

response coupling: responses change together (HR up, BP up).

response fractionation: responses change independently (HR down, BP up).

resonance frequency: the frequency at which a system, like the cardiovascular system, can be activated or stimulated.

right atrium: the upper chamber of the heart that receives deoxygenated blood and pumps it into the right ventricle.

right ventricle: the lower chamber of the heart that receives deoxygenated blood from the right atrium and pumps it into the pulmonary artery.

R-spike: the initial upward deflection in the QRS complex of the ECG.

sinoatrial (SA) node: the node of the heart that initiates each cardiac cycle through spontaneous depolarization of its autorhythmic fibers.

skin temperature: an indirect index of peripheral blood flow, which is primarily regulated by cutaneous arterioles.

spectral analysis: the division of HRV into its component rhythms that operate within different frequency bands.

S-T segment: an ECG structure that connects the QRS complex and the T wave. Ventricular contraction continues through the S-T segment.

stroke volume: the amount of blood ejected by the left ventricle during one contraction.

sympathetic cardiac accelerator nerves: nerves that arise from the medulla’s cardiovascular center that increase the rate of spontaneous depolarization in the SA and AV nodes and increase stroke volume by strengthening the contractility of the atria and ventricles.

systole: the contraction of the left ventricle.

systolic blood pressure (SBP): the force exerted by blood on arterial walls during contraction of the left ventricle.

T wave: an ECG structure that represents ventricular repolarization.

transit time (TT): in pulse wave velocity, the interval required for the pulse wave to move between two points along the arterial system.

tunica externa: external layer of an artery that of a connective tissue sheath.

tunica media: the middle layer of an artery composed of smooth muscle and elastic fibers and controlled by sympathetic constrictor fibers (C-fibers). This layer is a site of neurally-controlled vasoconstriction (decrease in lumen diameter and blood flow) in the digits.

ultra-low-frequency (ULF) band: the ECG frequency range below 0.003 Hz. Very slow biological processes that may contribute to this band include circadian rhythms, core body temperature, metabolism, and the renin-angiotensin system. There may also be PNS and SNS contributions.

vagal withdrawal: sympathetic suppression of parasympathetic activity associated with anxiety, effort, and fear.

vagus nerve: the parasympathetic vagus (X) nerve decreases the rate of spontaneous depolarization in the SA and AV nodes and slows the HR. Heart rate increases often reflect reduced vagal inhibition.

veins: blood vessels that route blood from tissues back to the heart and contain the same three layers found in arteries. These layers are thinner in veins due to lower pressure.

venule: a small vein (less than 2 millimeters in diameter) that collects blood from capillaries and delivers it to a vein. The low return pressure in these vessels requires valves that prevent backward blood flow.

very-low-frequency (VLF): the ECG frequency range of 0.003-.04 Hz may represent temperature regulation, gastric, plasma renin fluctuations, endothelial, physical activity influences, possible intrinsic cardiac nervous system, PNS, and SNS contributions.

REVIEW FLASHCARDS ON QUIZLET

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this module, describe how this module has changed your understanding of hand-warming. Also, explain when blood volume pulse feedback could be more useful than temperature biofeedback.

References

Agelink, M., Boz, C., Ullrich, H., & Andrich, J. (2002). Relationship between major depression and heart rate variability. Clinical consequences and implications for antidepressive treatment. Psychiatry Research, 113(1), 139-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00225-1

Akselrod, S., Gordon, D., Ubel, F. A., Shannon, D. C., Berger, A. C., & Cohen, R. J. (1981). Power spectrum analysis of heart rate fluctuation: A quantitative probe of beat-to-beat cardiovascular control. Science, 213, 220-222. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6166045

Andreassi, J. L. (2007). Psychophysiology: Human behavior and physiological response (5th ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, Inc.

Ballard, R. D. (1999). Sleep, respiratory physiology, and nocturnal asthma. Chronobiology International, 16(5), 565-580. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420529908998729

Bernardi, L., Valle, F., Coco, M., Calciati, A., & Sleight, P. (1996). Physical activity influences heart rate variability and very-low-frequency components in Holter electrocardiograms. Cardiovascular Research, 32, 234-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/0008-6363(96)00081-8

Bernardi, L., Gabutti, A., Porta, C., & Spicuzza, L. (2001). Slow breathing reduces chemoreflex response to hypoxia and hypercapnia, and increases baroreflex sensitivity. Journal of Hypertension, 19(12), 2221-2229. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-200112000-00016

Berntson, G. G., Bigger, J. T., Eckberg, D. L., Grossman, P., Kaufmann, P. G., Malik, M., Nagaraja, H. N., Porges, S. W., Saul, J. P., Stone, P. H., & van der Molen, M. W. (1997). Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology, 34(6), 623-648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x

Berntson, G. G., Quigley, K. S., & Lozano, D. (2007). Cardiovascular psychophysiology. In J. T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, & G. G. Berntson (Eds.). Handbook of psychophysiology (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bigger, J., Fleiss, J., Rolnitzky, L., & Steinman, R. (1993). The ability of several short-term measures of RR variability to predict mortality after myocardial infarction. Circulation, 88, 927-934. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.88.3.927

Bigger, J., Fleiss, J., Steinman, R., Rolnitzky, L., Kleiger, R., & Rottman, J. (1992). Frequency domain measures of heart period variability and mortality after myocardial infarction. Circulation, 85, 164-171. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.85.1.164

Bigger, J. T., Fleiss, J. L., Steinman, R. C., Rolnitzky, L. M., Schneider, W. J., & Stein, P. K. (1995). RR variability in healthy, middle-aged persons compared with patients with chronic coronary heart disease or recent acute myocardial infarction. Circulation, 91(7), 1936-1943. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.91.7.1936

Breit, S., Kupferberg, A., Rogler, G., & Hasler, G. (2018). Vagus nerve as modulator of the brain-gut axis in psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044

Carney, R. M., Blumenthal, J. A., Stein, P. K., Watkins, L., Catellier, D., Berkman, L. F., Czajkowski, S.M., O'Connor, C., Stone, P. H., & Freedland, K. E. (2001). Depression, heart rate variability, and acute myocardial infarction. Circulation, 104(17), 2024-2028. https://doi.org/10.1161/hc4201.097834

Casolo, G., Balli, E., Taddei, T., Amuhasi, J., & Gori, C. (1989). Decreased spontaneous heart rate variability in congestive heart failure. The American Journal of Cardiology, 64(18), 1162-1167. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(89)90871-0

Combatalade, D. (2010). Basics of heart rate variability applied to psychophysiology. Thought Technology Ltd.

DeBoer, R. W., Karemaker, J. M., & Strackee, J. (1987). Hemodynamic fluctuations and baroreflex sensitivity in humans: A beat-to-beat model. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 253(22), H680-H689. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.3.h680

Del Pozo, J. M., & Gevirtz, R. N. (2003). Complementary and alternative care for heart disease. Biofeedback, 31(3), 16-17.

Del Pozo, J. M., Gevirtz, R. N., Scher, B., & Guarneria, E. (2004). Biofeedback treatment increases heart rate variability in patients with known coronary artery disease. American Heart Journal, 147(3), G1-G6. 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.08.013

Drew, B. J., Califf, R. M., Funk, M., Kaufman, E. S., Krucoff, M. W., Laks, M. M., Macfarlane, P. W., Sommargren, C., Swiryn, S., Van Hare, G. F., American Heart Association, & Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young (2004). Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: An American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the young. Circulation, 110(17), 2721-2746. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000145144.56673.59

Fox, S. I., & Rompolski, K. (2022). Human physiology (16th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Gellhorn, E. (1957). Autonomic imbalance and the hypothalamus: Implications for physiology, medicine, psychology, and neuropsychiatry. Oxford University Press.

Gevirtz, R. (2013). The nerve of that disease: The vagus nerve and cardiac rehabilitation. Biofeedback, 41(1), 32-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.1.01

Gevirtz, R. N. (2000). Resonant frequency training to restore homeostasis for treatment of psychophysiological disorders. Biofeedback, 27, 7-9. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009554825745

Gevirtz, R. N. (2003). The promise of HRV biofeedback: Some preliminary results and speculations. Biofeedback, 31(3), 18-19.

Gevirtz, R. N. (2005). Heart rate variability biofeedback in clinical practice. AAPB Fall workshop.

Gevirtz, R. N. (2011). Cardio-respiratory psychophysiology: Gateway to mind-body medicine. BFE conference workshop.

Gevirtz, R. N., & Lehrer, P. (2003). Resonant frequency heart rate biofeedback. In M. S. Schwartz, & F. Andrasik (Eds.). Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Gevirtz, R. N., Lehrer, P. M., & Schwartz, M. S. (2016). Cardiorespiratory biofeedback. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.). Biofeedback: A practitioner’s guide (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Giardino, N. D., Chan, L., & Borson, S. (2004). Combined heart rate variability and pulse oximetry biofeedback for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 29(2), 121-133.

Ginsberg, J. P., Berry, M. E., & Powell, D. A. (2010). Cardiac coherence and posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans. Alternative Therapies, 16(4), 52-60. PMID: 20653296

Goldstein, D. S., Bentho, O., Park, M. Y., & Sharabi, Y. (2011). Low-frequency power of heart rate variability is not a measure of cardiac sympathetic tone but may be a measure of modulation of cardiac autonomic outflows by baroreflexes. Exp Physiol, 96(12), 1255-1261. https://doi.org/10.1113/expphysiol.2010.056259

Hayano, J., & Yuda, E. (2019). Pitfalls of assessment of autonomic function by heart rate variability. J Physiol Anthropol, 38(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40101-019-0193-2.

Herbs, D., Gevirtz, R. N., & Jacobs, D. (1994). The effect of heart rate pattern biofeedback for the treatment of essential hypertension [Abstract]. Biofeedback and Self-regulation, 19(3), 281.

Hon, E. H., & Lee, S. T. (1963). Electronic evaluation of the fetal heart rate. VIII. patterns preceding fetal death, further observations. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 87, 814–826.

Ironson, G., Taylor, C. B., Boltwood, M., Bartzokis, T., Dennis, C., Chesney, M., Spitzer, S., & Segall, G. M. (1992). Effects of anger on left ventricular ejection fraction in coronary artery disease. American Journal of Cardiology, 70(3), 281-285. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(92)90605-x

Izzo, J. L., & Shykoff, B. E. (2001). Arterial stiffness: Clinical relevance, measurement, and treatment. Review Cardiovascular Medicine, 2(1), 29-34, 37-40. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20070080

Kazuma, N., Otsuka, K., Matsuoka, I., & Murata, M. (1997). Heart rate variability during 24 hours in asthmatic children. Chronobiol Int, 14, 597–606. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420529709001450

Khazan, I. (2013). The clinical handbook of biofeedback. Wiley-Blackwell.

Khazan (2019). A guide to normal values for biofeedback. In D. Moss & F. Shaffer (Eds.). Physiological recording technology and applications in biofeedback and neurofeedback (pp. 2-6). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Khazan, I. (2019). Biofeedback and mindfulness in everyday life. W. W. Norton & Company.

Kleiger, R. E., Miller, J. P., Bigger, J. T., & Moss, A. J. (1987). Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. American Journal of Cardiology, 59, 256-262. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(87)90795-8

Laborde, S., Mosley, E., & Mertgen, A. (2018). Vagal tank theory: The three Rs of cardiac vagal control functioning – resting, reactivity, and recovery. Front. Neursci., 12, 458. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00458

Lacey, J. I. (1967). Somatic response patterning and stress: Some revisions of activation theory. In M. H. Appley & R. Trumbell (Eds.), Psychological stress: Issues in research (pp 14-42). Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Lacey, J. I., & Lacey, B. C. (1964). Cardiac deceleration and simple visual reaction in a fixed foreperiod experiment. Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Psychophysiological Research, Washington, D.C.

Lehrer, P. M. (2007). Biofeedback training to increase heart rate variability. In P. M. Lehrer, R. M. Woolfolk, & W. E. Sime (Eds.). Principles and practice of stress management (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Lehrer, P. M. (2012). Personal communication.

Lehrer, P. M. (2013). How does heart rate variability biofeedback work? Resonance, the baroreflex, and other mechanisms. Biofeedback, 41(1), 26-31. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.1.02

Lehrer, P. M. (2020). HRV live discussion forum. AAPB annual meeting.

Lehrer, P. M., & Eddie, D. (2013). Dynamic processes in regulation and some implications for biofeedback and biobehavioral interventions. Applied Psychophysiology & Biofeedback, 38, 143-155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-013-9217-6

Lehrer, P., Karavidas, M. K., Lu, S. E., Coyle, S. M., Oikawa, L. O., Macor, M., Calvano, S. E., & Lowry, S. F. (2010). Voluntarily produced increases in heart rate variability modulate autonomic effects of endotoxin induced systemic inflammation: An exploratory study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 35(4), 303-315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-010-9139-5

Lehrer, P., Kaur, K., Sharma, A., Shah, K., Huseby, R., Bhavsar, J., & Zhang, Y. (2020).

Heart rate variability biofeedback improves emotional and physical health and performance:

A systematic review and meta-analysis. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. https://doi.org//10.1007/s10484-020-09466-z

Lehrer, P. M., Smetankin, A., & Potapova, T. (2000). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback therapy for asthma: A report of 20 unmedicated pediatric cases using the Smetankin method. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 25, 193-200. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009506909815

Lehrer, P. M., & Vaschillo, E. (2008). The future of heart rate variability biofeedback. Biofeedback, 36(1), 11-14.

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E., Vaschillo, B., Lu, S. E., Eckberg, D. L., Edelberg, R., Shih, W. J., Lin, Y., Kuusela, T. A., Tahvanainen, K. U. O., & Hamer, R. M. (2003). Heart rate variability biofeedback increases baroreflex gain and peak expiratory flow. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 796-805. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000089200.81962.19

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E. V., & Vaschillo, B. (2004). Heartbeat synchronizes with respiratory rhythm only under specific circumstances. Chest, 126(4), 1385-1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-3692(15)31329-5

Lehrer, P., Vaschillo, E., Vaschillo, B., Lu, S-E, Scardella, A., Siddique, M, & Habib, R. (2004). Biofeedback treatment for asthma. Chest, 126, 352-361. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.126.2.352

MacKinnon, S., Gevirtz, R., McCraty, R., & Brown, M. (2013). Utilizing heartbeat evoked potentials to identify cardiac regulation of vagal afferents during emotion and resonant breathing. Applied Psychophysiology & Biofeedback, 38, 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-013-9226-5

MacLean, B. (2004). The heart and the breath of love. Biofeedback, 32(4), 21-25.

Maver, J., Strucl, M., & Accetto, R. (2004). Autonomic nervous system activity in normotensive subjects with a family history of hypertension. Clinical Autonomic Research: Official Journal of the Clinical Autonomic Research Society, 14(6), 369-375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-004-0185-z

McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., & Tiller, W. A. (1995). The effects of emotions on short term power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability. American Journal of Cardiology, 76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80309-9

McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., Tomasino, D., & Bradley, R. T. (2006). The coherent heart. Institute of HeartMath.

McCraty, R., Atkinson M, Tomasino, D., & Bradley, R. T. (2009). The coherent heart: Heart-brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. Integral Review, 5(2), 10-115.

McCraty, R. & Shaffer, F. (2015). Heart rate variability: New perspectives on physiological mechanisms, assessment of self-regulatory capacity, and health risk. Glob Adv Health Med, 4(1). 46-61. https://doi.org/10.7453/gahmj.2014.073.

Moravec, C. S., & McKee, M. G. (2013). Biofeedback in heart failure: Psychophysiologic remodeling of the failing heart. Biofeedback, 41(1), 7-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.1.04

Moss, D. (2004). Heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback. Psychophysiology Today, 1, 4-11.

Nada, T., Nomura, M., Iga, A., Kawaguchi, R., Ochi, Y., Saito, K., Nakaya, Y., & Ito, S. (2001). Autonomic nervous function in patients with peptic ulcer studied by spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Journal of Medicine, 32(5-6), 333-347. PMID: 11958279

Nolan, J., Flapan, A. D., Capewell, S., MacDonald, T. M., Neilson, J. M., & Ewing, D. J. (1992). Decreased cardiac parasympathetic activity in chronic heart failure and its relation to left ventricular function. Br Heart J, 67(6), 482-485. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.67.6.482

Nunan, D., Sandercock, G. R. H., & Brodie, D. A. (2010). A quantitative systematic review of normal values for short-term heart rate variability in healthy adults. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 33(11), 1407-1417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02841.x

Ogletree-Hughes, M. L., Stull, L. B., Sweet, W. E., Smedira, N. G., McCarthy, P. M., & Moravec, C. S. (2001). Mechanical unloading restores beta-adrenergic responsiveness and reverses receptor down-regulation in the failing human heart. Circulation, 104, 881-886. https://doi.org/10.1161/hc3301.094911

Olshansky, B., Sabbah, H. N., Hauptman, P. J., & Colucci, W. S. (2008). Parasympathetic nervous system and heart failure: Pathophysiology and potential implications for therapy. Circulation, 118, 863-871. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.107.760405

Opthof, T. (2000). The normal range and determinants of the intrinsic heart rate in man. Cardiovascular Research, 45, 177-184. PMID: 10728332

Papillo, J. F., & Shapiro, D. (1990). The cardiovascular system. In J. T. Cacioppo & L. G. Tassinary (Eds.) Principles of psychophysiology: Physical, social, and inferential elements (pp. 456 - 512). Cambridge University Press.

Peek, C. J. (2016). A primer of traditional biofeedback instrumentation. In M. S. Schwartz, & F. Andrasik (Eds.). (2016). Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Lin, I., Tylova, H., & Moss, D. (2007). Is there more to blood volume pulse than heart rate variability, respiratory sinus arrhythmia, and cardio-respiratory synchrony? Biofeedback, 35(2), 54-61.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. W. Norton & Company.

Ridker, P. M., Rifai, N., Stampfer, M. J., & Hennekens, C. H. (2000). Plasma concentration interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation, 101(15), 1767-1772. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.15.1767

Roach, D., Wilson, W., Ritchie, D., & Sheldon, R. (2004). Dissection of long-range heart rate variability: Controlled induction of prognostic measures by activity in the laboratory. J Am Coll Cardiol, 43(12), 2271-2277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.050

Shaffer, F., McCraty, R., & Zerr, C. L. (2014). A healthy heart is not a metronome: An integrative review of the heart’s anatomy and heart rate variability. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01040

Shaffer, F., Meehan, Z. M., & Zerr, C. L. (2020). A critical review of ultra-short-term heart rate variability norms research. Front. Neurosci., 29. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.594880

Shaffer, F., & Moss, D. (2006). Biofeedback. In Y. Chun-Su, E. J. Bieber, & B. Bauer (Eds.). Textbook of complementary and alternative medicine (2nd ed.). Informa Healthcare.

Stauss, H. M. (2003). Heart rate variability. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 285, R927-R931. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00452.2003

Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology (1996). Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation, 93, 1043-1065. PMID: 8598068

Taylor, J. A., Carr, D. L., Myers, C. W., & Eckberg, D. L. (1998). Mechanisms underlying very-low-frequency RR-interval oscillations in humans. Circulation, 98, 547-555. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.98.6.547

Taylor, S. E. (2006). Tend and befriend: Biological bases of affiliation under stress. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(6), 273-277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00451.x

Thayer, J. F., Ahs, F., Fredrikson, M., Sollers, J. J., & Wager, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 36, 747-756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.009

Thayer, J. F., & Lane, R. D. (2000). A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61, 201-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00338-4

Thayer, J. F., Yamamoto, S. S., & Brosschot, J. F. (2010). The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Int J Cardiol, 141(2), 122-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.09.543

Tortora, G. J., & Derrickson, B. H. (2021). Principles of anatomy and physiology (16th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Umetani, K., Singer, D. H., McCraty, R., & Atkinson, M. (1998). Twenty-four hour time domain heart rate variability and heart rate: Relations to age and gender over nine decades. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 31(2), 593-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00554-8

Vaschillo, E., Lehrer, P., Rishe, N., & Konstantinov, M. (2002). Heart rate variability biofeedback as a method for assessing baroreflex function: A preliminary study of resonance in the cardiovascular system. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 27, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014587304314

Vaschillo, E., Vaschillo, B., & Lehrer, P. (2004). Heartbeat synchronizes with respiratory rhythm only under specific circumstances. Chest, 126, 1385-1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-3692(15)31329-5

Vaschillo, E. G., Vaschillo, B., & Lehrer, P. M. (2006). Characteristics of resonance in heart rate variability stimulated by biofeedback. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 31(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-006-9009-3

Vaschillo, E. G., Vaschillo, B., Pandina, R. J., & Bates, M. E. (2011). Resonances in the cardiovascular system caused by rhythmical muscle tension. Psychophysiology, 48, 927–936. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01156.x

Walløe, L. (2016). Arterio-venous anastomoses in the human skin and their role in temperature control. Temperature (Austin), 3(1), 92-103. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F23328940.2015.1088502

Widmaier, E. P., Raff, H., & Strang, K. T. (2019). Vander's human physiology: The mechanisms of body function (15th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Yasuma, F., & Hayano, J. (2004). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: Why does the heartbeat synchronize with respiratory rhythm? Chest, 125(2), 683-690. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.125.2.683

B. RESPIRATORY ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

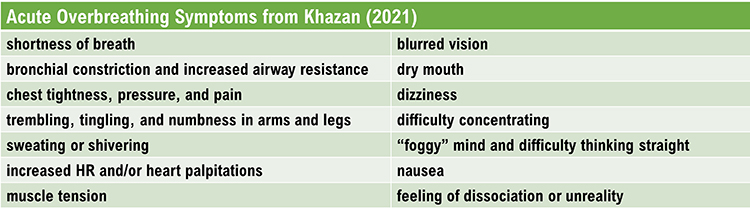

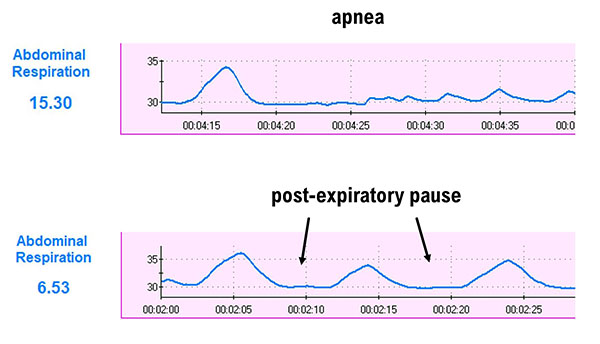

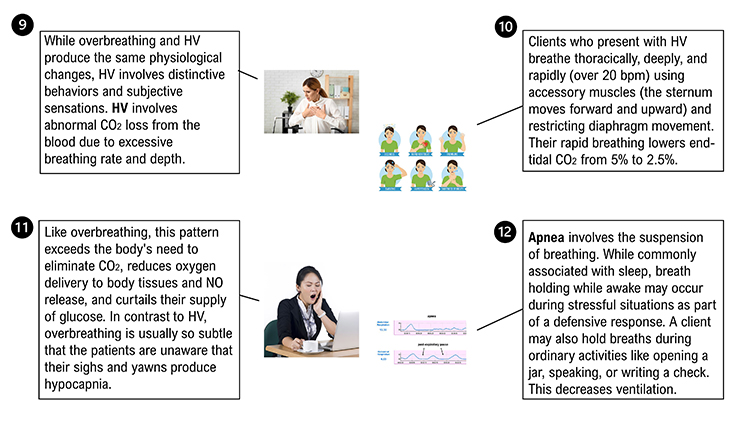

Healthcare providers who do not routinely observe their patients' breathing may miss helpful diagnostic information. Breathing assessment can provide useful information regarding a client's emotional state and respiratory mechanics. Frequent sighs could signal depression. Low exhaled CO2 could indicate overbreathing, which can cause diverse symptoms. While medical disorders fall outside most practitioners' scope of practice, they can share breathing assessment findings relevant to medical disorders with their client's physician. For example, a physician managing a client's hypertension might appreciate information about their apnea since it can contribute to this problem.

Overbreathing may be the most common dysfunctional breathing pattern that can subtly reduce CO2 and produce diverse medical and psychological symptoms due to its disruption of homeostasis (Khazan, 2021). Graphic © Yuliya Evstratenko/ Shutterstock.com.

This section covers Respiratory Physiology and Disordered Breathing.

Respiratory Physiology

Breathing Ensures Healthy CO2 Levels

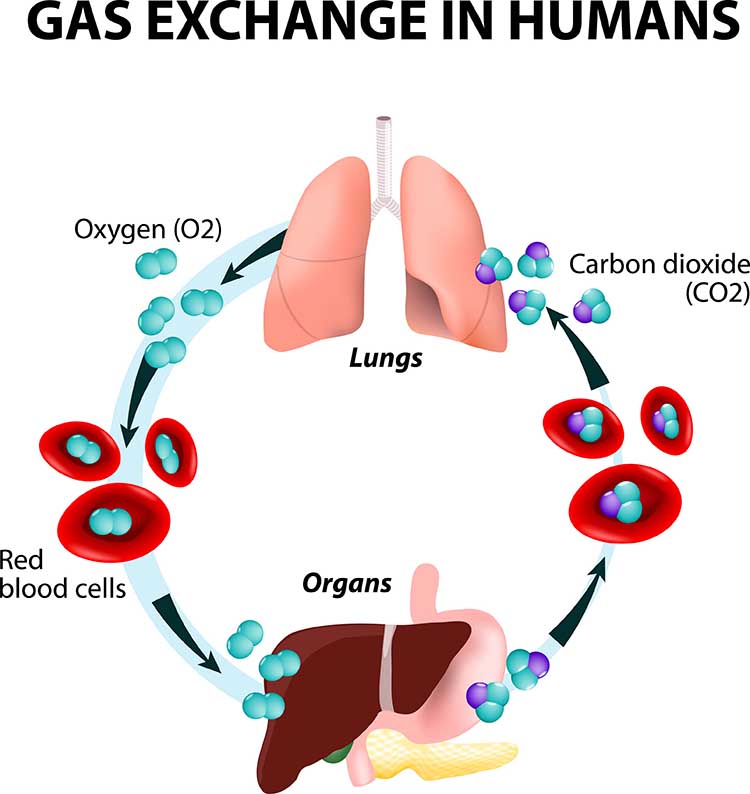

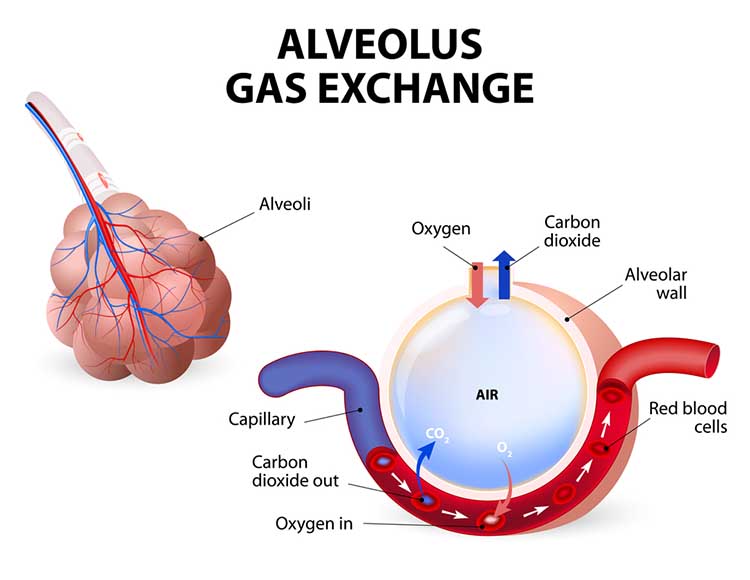

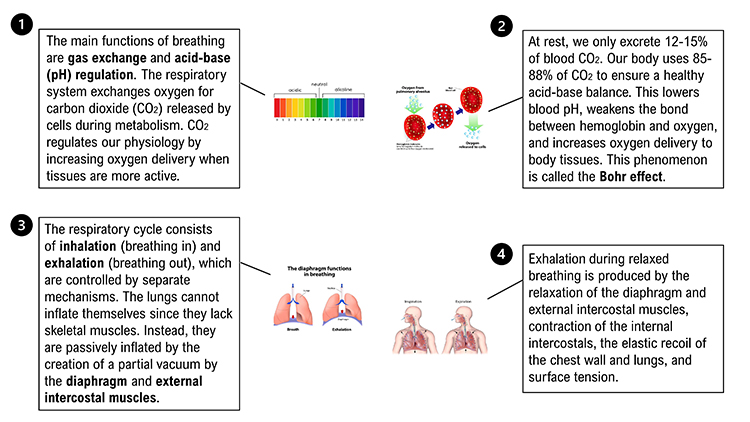

The main functions of breathing are gas exchange and acid-base (pH) regulation. The respiratory system exchanges oxygen for carbon dioxide (CO2) released by cells during metabolism. CO2 regulates our physiology by increasing oxygen delivery when tissues are more active. Our body uses 85-88% of CO2 to ensure a healthy acid-base balance, making gas exchange possible through the Bohr effect (Khazan, 2021).Dr. Khazan explains internal respiration © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. You can enlarge the video by clicking on the bracket icon at the bottom right of the screen. When finished, click on the ESC key.

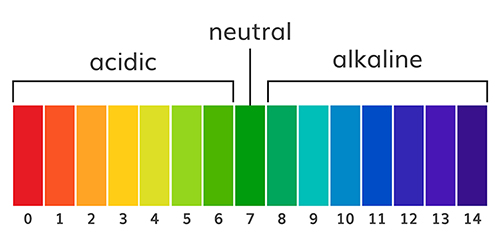

The abbreviation pH refers to the power of hydrogen, which is the concentration of hydrogen ions. Acidic solutions have a low pH (< 7) due to a high concentration of hydrogen ions. A neutral solution of distilled water has a pH of 7. Alkaline or basic solutions have a high pH (>7) due to a low concentration of hydrogen ions. The pH level regulates oxygen and nitric oxide release. Graphic © AlexVector/ Shutterstock.com.

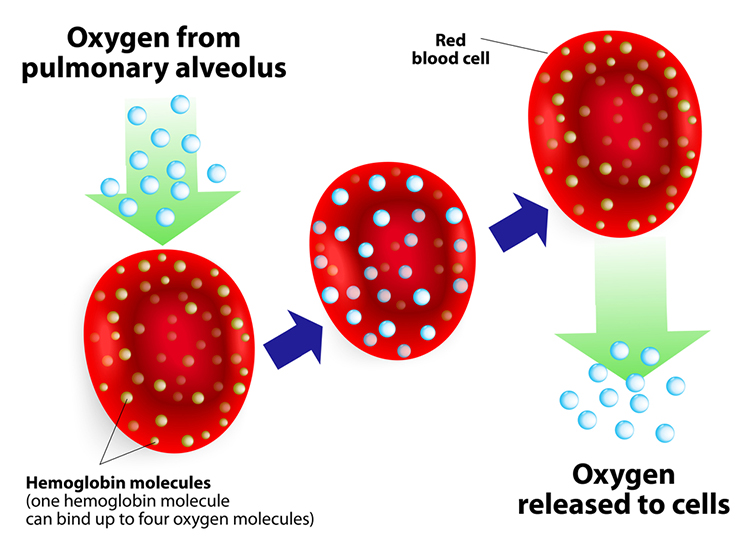

Hemoglobin molecules on red blood cells transport oxygen and nitric oxide through the bloodstream. One hemoglobin molecule can carry four oxygen molecules. Red blood cell graphic © royaltystockphoto.com/ Shutterstock.com.

.jpg)

Relaxed breathing increases the carbon dioxide concentration of arterial blood compared to thoracic breathing. At rest, we only excrete 12-15% of blood CO2. Conserving CO2 lowers blood pH, weakens the bond between hemoglobin and oxygen, and increases oxygen delivery to body tissues. This phenomenon is called the Bohr effect. Check out MEDCRAMvideos YouTube lecture Oxygen Hemoglobin Dissociation Curve Explained Clearly!

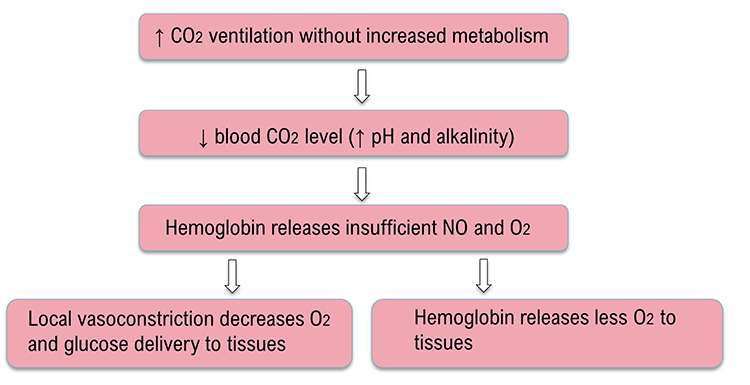

Conversely, low CO2 levels due to overbreathing or hyperventilation raise blood pH and reduce oxygen delivery to body tissues since oxygen remains tightly bound to the hemoglobin molecules (Fox & Rompolski 2022). Graphic © Designua/Shutterstock.com.

Conserve CO2

We do not need more oxygen! (Khazan, 2021). Near sea level, the air healthy clients inhale contains 21% oxygen, while the air they exhale has 15%. We only use ¼ of inhaled oxygen and don’t need more. We need to conserve CO2 by retaining 85-88% of it.Breathing Serves More Than Gas Exchange

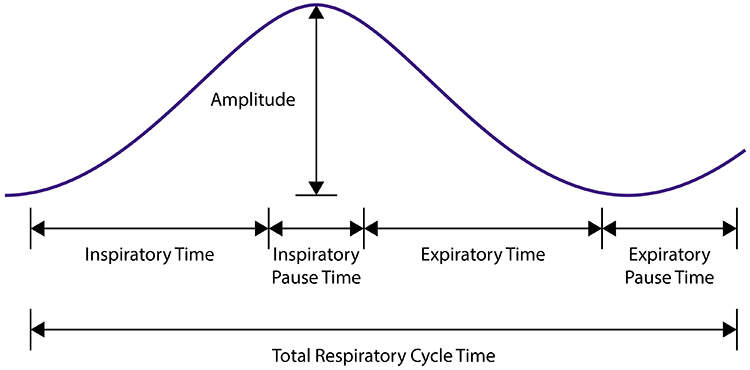

The respiratory system also delivers odorants to the olfactory epithelium, produces the airway pressure required for speech, anticipates cognitive and skeletal muscle metabolic demands, and helps to modulate systems regulated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), especially the cardiovascular system. Respiration is an important regulator of heart rate variability, consisting of beat-to-beat changes in the heart rhythm (Lorig, 2007). Check out the YouTube video The Respiratory System.The Respiratory Cycle

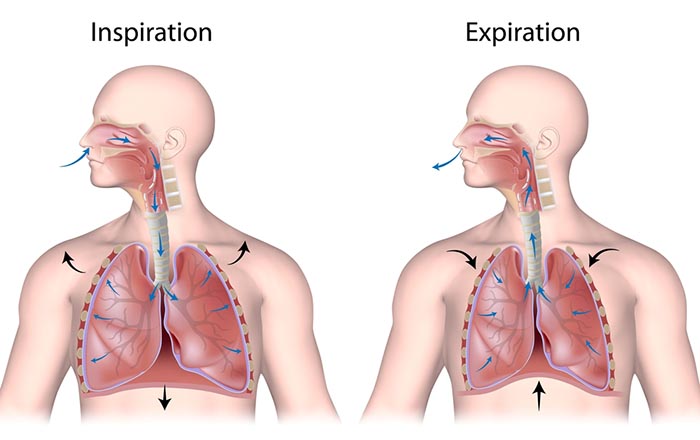

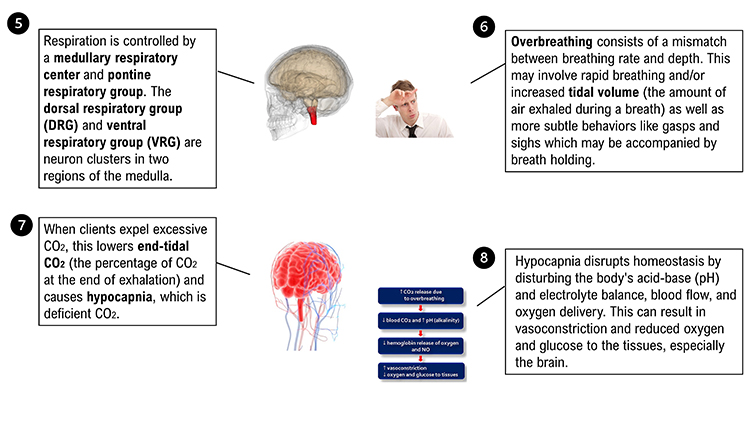

We breathe about 20,000 times a day. Typical adult resting breathing rates are 12-14 breaths per minute (bpm; Khazan, 2019a). Disorders that affect respiration may raise rates to 18-28 bpm (Fried, 1987; Fried & Grimaldi, 1993).The respiratory cycle consists of inhalation (breathing in) and exhalation (breathing out), which are controlled by separate mechanisms. Animation © weicheltfilm/iStockphoto.com.

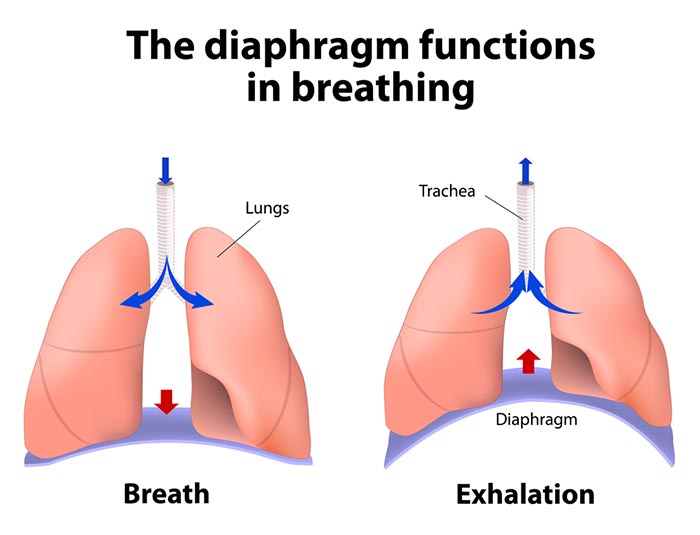

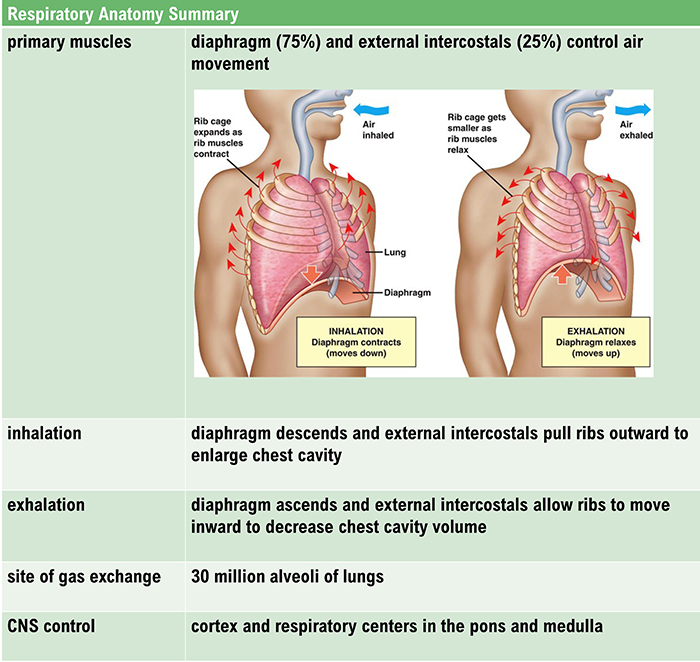

The lungs cannot inflate themselves since they lack skeletal muscles. Instead, they are passively inflated by creating a partial vacuum by the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles (Gevirtz, Schwartz, & Lehrer, 2016).

During inhalation, contraction by the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles ventilate the lungs. Check out the Blausen Intercostals animation.

The dome-shaped diaphragm muscle plays the lead role during inhalation. The diaphragm comprises the floor of the thoracic cavity. When the diaphragm contracts, it flattens, and its dome drops, increasing the thoracic cavity volume. Contraction of the diaphragm pushes the rectus abdominis muscle of the stomach down and out. Check out the Blausen Diaphragm animation.

In the animation below, watch the lungs inflate as the diaphragm descends. Animation © look_around/iStockphoto.com.

In relaxed breathing, a 1-cm descent creates a 1-3 mmHg pressure difference and moves 500 milliliters of air. In labored breathing, a 10-cm descent produces a 100-mmHg pressure difference and transports 2-3 liters of air. The diaphragm accounts for about 75% of air movement into the lungs during relaxed breathing.

The external intercostals play a supporting role during inhalation. External intercostal muscle contraction pulls the ribs upward and enlarges the thoracic cavity. The external intercostals account for about 25% of air movement into the lungs during relaxed breathing.

The contraction of the diaphragm and the external intercostals expands the thoracic cavity, increases lung volume, and decreases the pressure within the lungs below atmospheric pressure. This pressure difference causes air to inflate the lungs until the alveolar pressure returns to atmospheric pressure.

During forceful inhalation, accessory muscles of inhalation (sternocleidomastoid, scalene, pectoralis major and minor, serratus anterior, and latissiumus dorsi) also contract (Khazan, 2021). Graphic © Designua/Shutterstock.com.

The dome-shaped diaphragm muscle ascends during normal expiration.